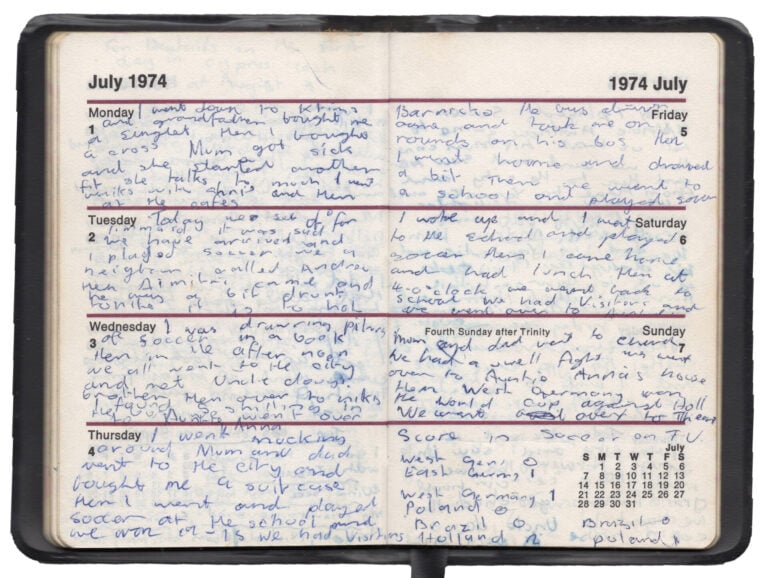

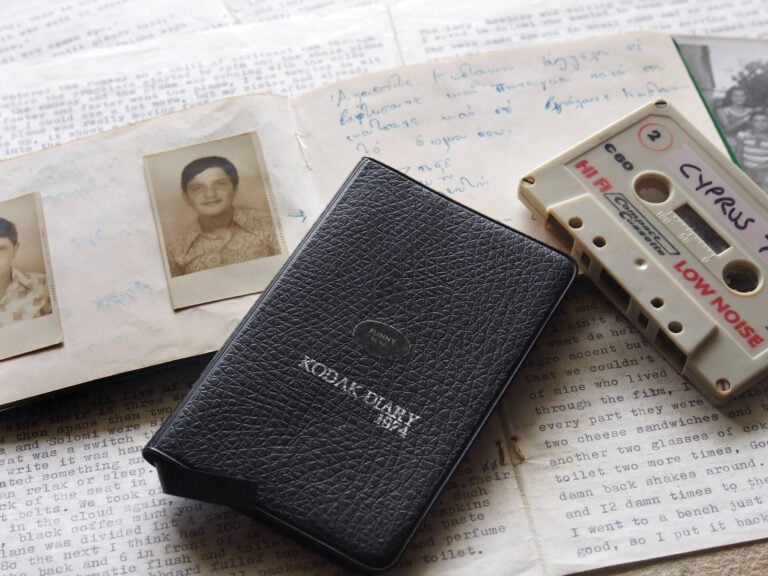

My first experience of Cyprus took place in 1974 during an ill-fated family holiday. I was just a teenager. We were there between April and August including the coup d’état and the first two weeks of the invasion. I can’t believe that was almost 51 years ago. To tell you the truth, I was worried that I might start to forget what really happened that year. Then this week I found the little black diary that I kept in Cyprus to write down my thoughts and daily events. I also found an old cassette tape that had some live recordings and a typed account of my trip to Cyprus written after my return to Australia.

Well, let me tell you – these precious items have brought back so many memories. Memories that I may have supressed. To think, that I almost threw my diary away after my uncle warned me that I would be arrested at the airport if the authorities found it on me. I’ll explain what happened later.

So today, I have decided for the first time to share my 1974 experience with you.

I hope you don’t mind.

THE COUP D’ÉTAT

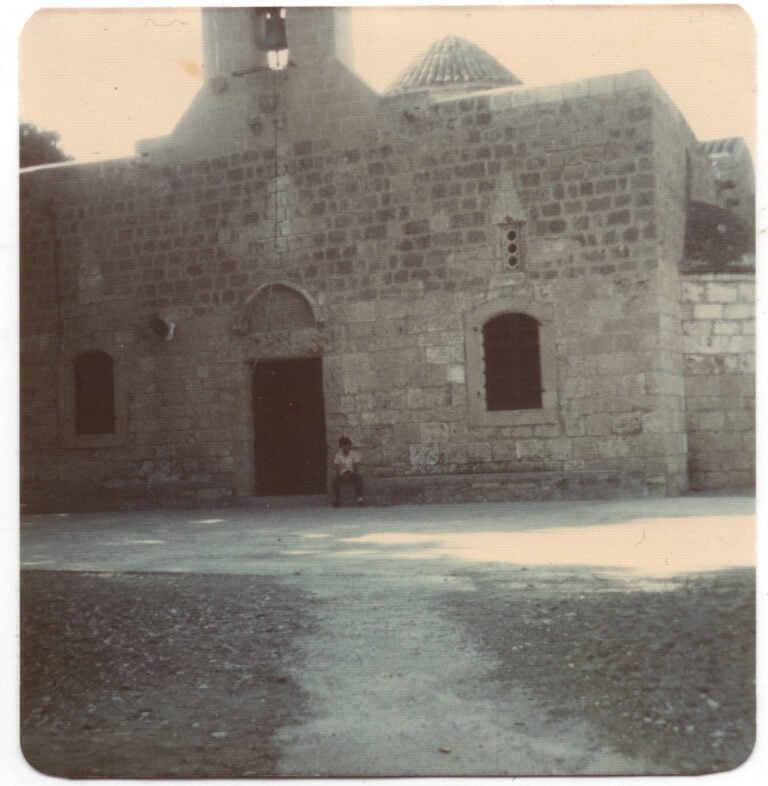

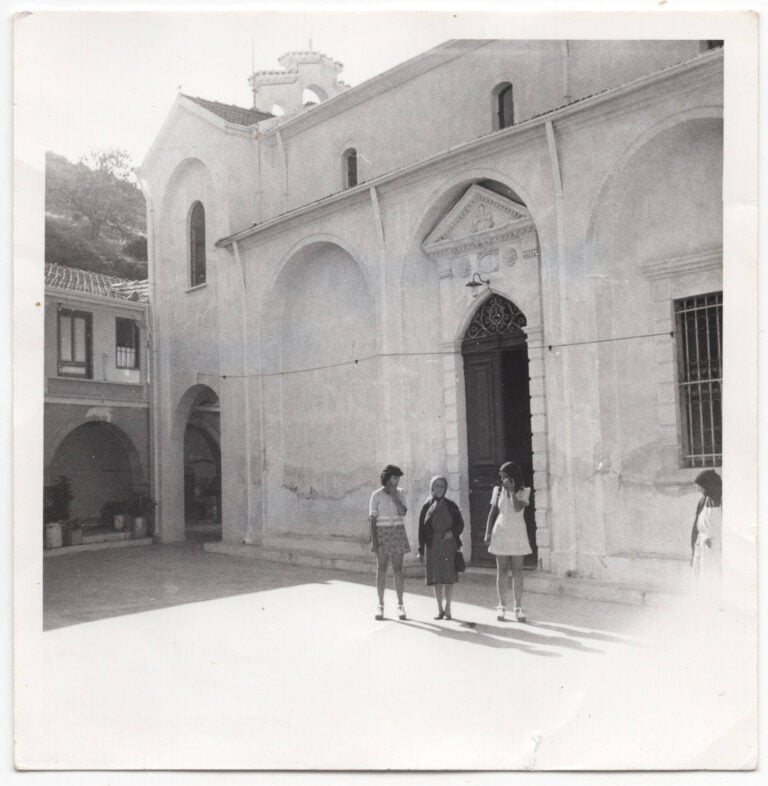

On the 6th June 1974, my parents rented a small bungalow on Londinou Street in Limassol. We knew it as London Street. We had been living in Cyprus since April and had travelled all over the island in a once in a life time adventure. Indeed, I was having a great time.

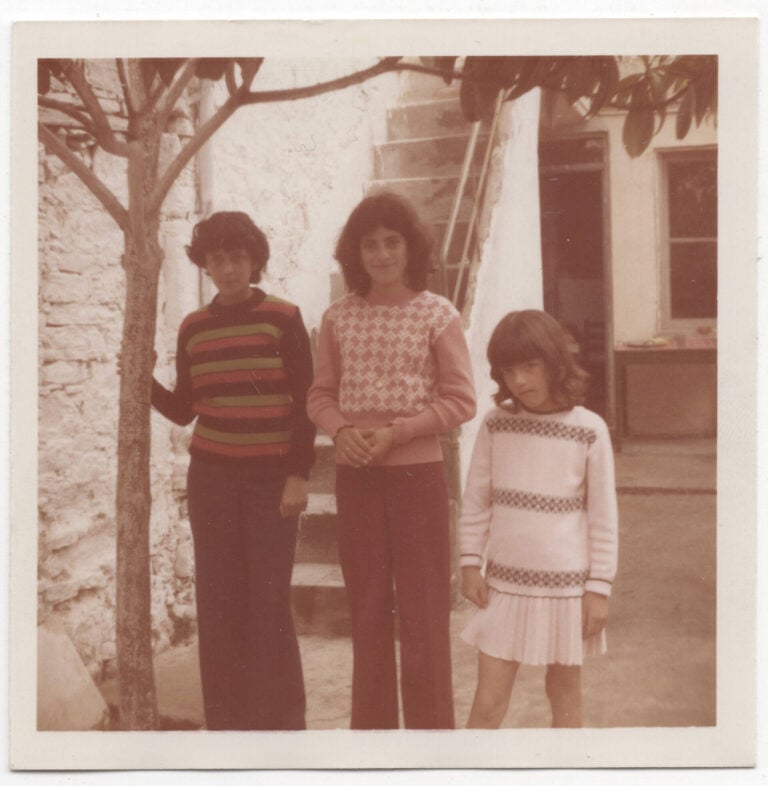

It was my parent’s wish to show my three sisters and I the country of their birth and of course, our ancestral home. In fact, by the time we settled in Limassol, my parents were seriously considering moving back to Cyprus for good. Unfortunately, the civil unrest followed by a Junta-led coup and the Turkish invasion put an end to that dream.

But more about that later.

London Street was located in the suburb of Agios Ioannis near Arch. Makarios III Street (also known as Leoforou). Our bungalow was actually behind a large house that was owned by our landlord Aristos and his wife Stavroulla.

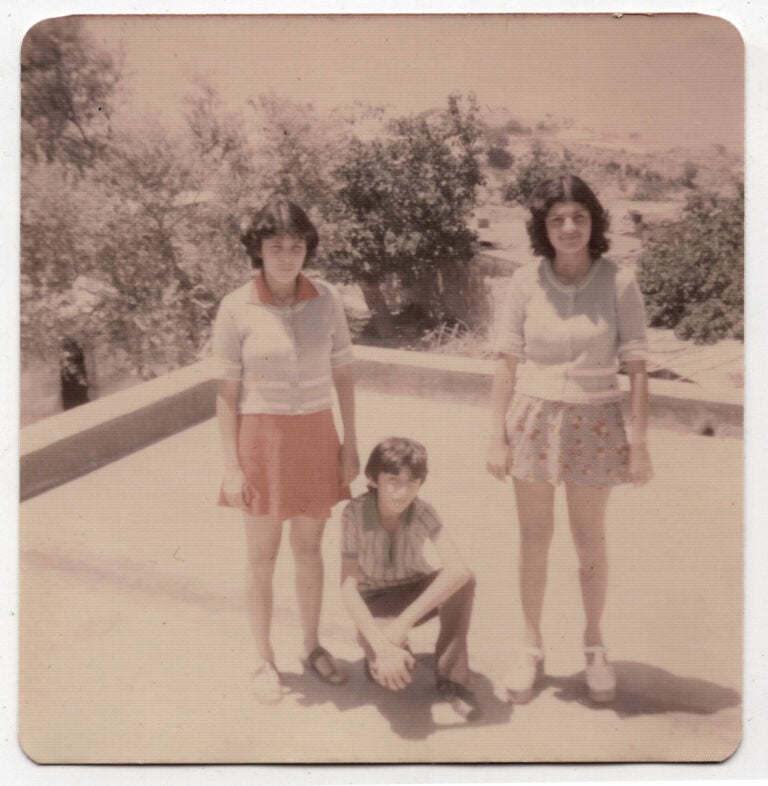

What I found remarkable about London Street (and Cyprus in general), was just how easy it was to make friends. No sooner did we move into the neighbourhood when all the local boys and girls came to greet us to make us feel welcome. Within a day, I was friends with Dimitri and his brother Sophoclis, Kostas, Andreas, Jason and Nicos. I was regularly invited to their houses and to play football (soccer) on a dusty patch of dirt near our street. My sisters also made friends quickly but at times were also distracted by a few of the handsome older boys in the neighbourhood.

London Street was also such a different place compared to my street in the northern suburbs of Melbourne. For instance, it took me less than a week to meet every single person that lived in this street. Sure, I knew my neighbours in Melbourne but only from a distance. In Cyprus, you only had to smile at a neighbour and they would invite you to come in and share a meal. I remember there was a baker on London Street where I was sent each morning to buy fresh bread. The baker had five or six children and my sisters and I spent many enjoyable hours with them. By the way, the bread from that bakery remains the best bread I have ever tasted.

Not far from our house lived a lovely English couple. I think the husband worked at RAF Akrotiri. I remember that his wife was often in the front yard of their rental property with a young child and she enjoyed having conversations with the new Australian neighbours.

I can honestly say that up until the 15th July, I spent most of my time roaming the backstreets of Agios Ioannis with Andreas and Dimitri and my other friends. Sometimes we would ride our bikes down to Café Pari, (around two miles away) to play on the soccer tables or to eat ice-cream. Other times we would sit in the shade of a palm tree and just talk nonsense. My language skills improved considerably. I also learnt quite a few dirty phrases and swear words. Those young Cypriot boys sure did know how to swear. They seemed to curse the ‘black devil’ an awful lot.

Front row: My friend Andrew and me (right). July 1974.

When I wasn’t kicking a ball with my friends, I was watching a match on TV with them. My love for football (soccer) intensified when the World Cup tournament began (in West Germany) on the 13th June. I was rooting for West Germany while my friend and neighbour Dimitri was hoping that Brazil would win. Every time there was a match on TV, Dimitri would invite me to his house to watch it. I have very fond memories of those hot summer days, sitting in Dimitri’s lounge room watching our heroes like Franz Beckenbauer, Gerd Müller and Johan Cruyff on his little black and white TV. Sometimes his mother would serve us watermelon and other refreshing treats. Life was pretty good.

As far as the football teams in Cyprus, I was barracking for Omonia, much to the disappointment of my left-wing friends. For me it was just football but to them – the team you supported represented your allegiance to a certain political party in Cyprus.

Sometimes at Dimitri’s house we would sit on his front porch drinking rose cordial while we listen to popular tunes on the radio. Two particular songs that caught my fancy were ‘Thaskala, Thaskala’ by Stelios Chiotis and ‘Ah Mustafa’ by Oula Baba.

It was sometime in early July, when I started hearing loud noises at night. The noises sounded like gunfire but my father and older sister Helen tried to reassure me that the ‘bang-bang’ sounds were just trucks backfiring or getting flat tyres. After the third night of hearing these loud bangs I said to my father, ‘geez, there’s an awful lot of trucks getting flat tyres in Limassol.” He didn’t respond.

It was only after I quizzed the neighbourhood kids the next day, when I discovered that Cypriots were actual shooting at each other because of their political views and ideologies. ‘Has everybody gone nuts?’ I thought. I remember as soon as we landed in Cyprus my father warned me to keep away from anyone who wanted to discuss politics. “Keep away, and keep your opinions to yourself,” he said sternly. “This is not Australia. We are not in Australia anymore.” I had also been warned by my cousins in Paphos that sometimes young men in Cyprus uses guns to prove a point.

My father had nothing to worry about. Despite my young age, I knew enough to keep away from debates about politics. Besides, as a young teenager boy, I only cared about football, souvla, Greek sweets and (according to my diary), a sweet young girl named Panayiota who lived opposite my Aunt Helen’s house in Tsada. But that’s another story altogether.

On Sunday the 14th of July, my family attended a cousin’s wedding in Limassol. Everybody was is high spirits. This was my first real experience of a Cypriot wedding and I was pleased to witness all the traditional symbolism and culture surrounding the bride and groom. There was lots of food of course, plus live music and plenty of dancing. As I recall, the reception took place outdoors, on the street under the stars. A gentle cool breeze was welcomed by the guests after another hot summer day.

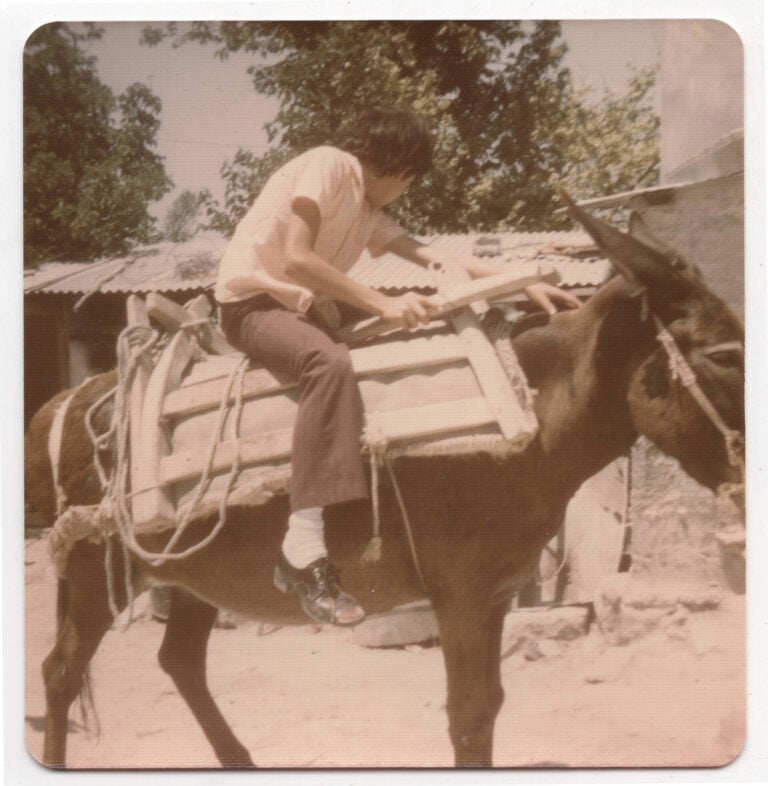

I had already experienced a number of village festivals whilst in Cyprus and even a funeral in Arsos. Where ever I went in Cyprus and whatever I did, I always allowed myself to become intoxicated by the culture and therefore, I was becoming more Cypriot by the day.

On the morning of the 15th of July, I woke up to the sound of military (martial) music blaring from various radios in the neighbourhood. I think the station was Radio Cyprus. Just after 9am, a news flash interrupted the gloomy tunes announcing that President Archbishop Makarios had been shot dead. Almost immediately a chorus of wails and screams could be heard in the neighbourhood. Then I saw quite a few women rush out of their homes to hug and console one another. My mother immediately collapsed to her knees and started to pray. My father, as always, went silent however his face betrayed his emotions and he genuinely looked terrified.

I ran out onto the street to meet my friends and they all took turns to try and explain to me what was going on. I sat and listened and kept saying, “this is nuts. Why would the Cypriots do this?”

My poor friends struggled to make me comprehend what was happening in Cyprus. I don’t think even THEY could comprehend what was taking place in Nicosia. I remember that most of them believed that the worst was over and things would start to improve.

The military music continued all morning and was only interrupted by further gloomy news reports and announcements. Then a curfew across the island was imposed.

That night as I was getting ready for bed I looked out of my window and saw our landlord Aristos climbing onto the roof of his house. I was shocked to see that he was carrying a gun.

Moments later the deafening sound of gunfire was heard. “What the hell is going on now?” I thought. The noise of gunfire was so loud I had to cover my ears with my hands. My parents tried their best to console me and my sisters. Their efforts were fruitless. My sisters were sobbing and shrieking (I think one of them threw up). My mother was on her knees again, with a bible in her hand praying furiously to Jesus, Mary and God. My father was in the kitchen, sitting silently and looking worse for wear while I was tinkering with our cassette radio player trying to record the sounds of gunfire in the night. Somehow, I was aware that this was a significant historical moment – even though I didn’t fully understand what was happening. Was I scared? I honestly can’t remember – but I’m pretty sure I was.

Late on Monday night, we were awoken by the sounds of footsteps on the roof of our bungalow. Lots of footsteps. My sister Helen thought it was just cats walking up and down the roof. Perhaps it was Aristos and his friends.

The next morning, (Tuesday, 16th July) I awoke to the voice of Makarios on the radio. “Cypriot people. This is Makarios. I am alive. I am not dead.” I couldn’t believe my ears. He was alive. Makarios was alive. His famous speech was immediately followed by lots of yelping and celebrating in the street. Once again my mother crossed herself and started to pray for a peaceful resolution.

In that moment I felt sorry for my mother. She had tried her best to prepare us for the trip to Cyprus and to promote the many attributes and benefits of living on the island. I know she always dreamed of moving back and raising her family in Limassol. God only knew what she was thinking now. This event was really going to test her faith.

Later that day, I was standing in the street with my friends Nicos, Dimitri and Andreas when a helicopter flew overhead. An elderly neighbour cried out that Makarios was in the helicopter but I’m not really sure if I believed him.

On Wednesday the 17th of July I decided to go for a bike ride. I’m not quite sure why I decided to go for a bike ride – especially during a curfew – but nevertheless, I managed to find myself in a deserted schoolyard at the Agios Ioannis Elementary School. To my surprise there were plenty of empty bullet casings scattered across the ground so I decided to park my bike and collect a few. Perhaps I was thinking that the bullet casings might one day become a wonderful souvenir or memento. I remember that the school wall behind me was pockmarked with bullet holes.

As I was collecting the bullet shells, an army Jeep drove past with some soldiers wearing black berets sitting in the open section of the vehicle. They seemed to be in high spirits. Suddenly one of the soldiers raised his machine gun and fired a few rounds above my head. The bullets whizzed past me and hit the pockmarked wall tearing off more fragments of render.

Whether the soldier deliberately tried to scare me or whether he fired at the wall without noticing me, I’ll never know. What I do know is this. I panicked, dropped my bullet casings and rode my bike as quick as I could towards my house. I remember looking back and seeing the soldiers laughing. Some of them were shouting and calling out to me, but I cannot recall what they were saying. When I got home, exhausted and still terrified after my ordeal, my father greeted me with a slap. He was angry that I had broken the curfew and frightened that I could have been killed. I received a stern warning from my parents and told to get rid of my ridiculous urge to seek adventure.

That night I spotted our landlord on the roof of his house again with his gun. I later found out that he was shooting at the Agios Ioannis Police Station. I was perplexed. “What the hell was he up too? Who was this man?” Nothing made any sense to me. During the day he seemed like such a mild-mannered and pleasant man while at night he became a guerrilla fighter.

By Thursday the 18th July, my father had decided ‘enough is enough’ and that we should pack all our bags and try to flee the island. The plan was to get up early the next morning and head for the airport in Nicosia to try and see if we could get a flight out of the country.

We spent Friday night packing our bags and saying good bye to our friends and relatives. It was a very bittersweet moment for me. On one hand, I was relieved and desperate to leave the island while on the other hand I was heartbroken and sad to leave my friends and relatives behind. ‘What a mess,’ I thought. ‘What an absolute mess.’ I can vaguely remember saying to my father, rather sarcastically, “thanks a lot dad for bringing us to a war zone.” Little did I know what was to come.

We spent Friday night at my Aunt Augusta and Uncle Andrew’s house with a few other relatives. Their house was located on Spirou Stathopoulou Street. I sat quietly watching and listening to the older men in the room. They sat together, hunched over with forlorn expressions on their faces muttering something about Nicos Sampson and the Greek Junta. I couldn’t fully understand what they were saying only that Cyprus was doomed. The older women (including my mother) were also lamenting about the future of Cyprus but instead of expressing any political views, they kept making the sign of the cross and calling out to the Virgin Mary to save the people.

At some point in the evening I must have mentioned to my Uncle Andrew that I was writing a personal diary and had documented what had taken place that week. His face suddenly turned fierce and he pleaded with me to destroy the diary. When I asked him why? he said something about being arrested at the airport and charged with espionage if I was caught with such a book. That night, I kept thinking about my uncle’s warning. I decided to tear out just the pages relating to the last five days and threw them in the bin. I then carefully buried my diary deep in the recess of my suitcase.

Tearing out those pages in my diary is something that I have come to regret. Although my memories of that fateful week are still rather vivid, nothing can compare to the detailed first-hand account that I had written in my diary that week.

The next morning (Saturday, 20th July) at approximately 6.30am, we loaded our suitcases and bags into a rented taxi and kissed our relatives goodbye. ‘Ο θεός μαζί σας. Ο θεός μαζί σας.’ (God be with you) my Aunt Augusta cried as she hugged and kissed each member of my family. The loudest sobs were reserved for her sister Panayiota – my mother.

There were plenty of tears all round. Even the men were crying. The taxi driver tooted his horn and we set off for Nicosia. There was another passenger in the taxi with us – an older gentleman who was going to Nicosia to find his son. Apparently the son’s whereabouts were unknown since the coup on Monday.

Approximately, 30 minutes into the trip, the taxi driver turned on his car radio. The silence of the cabin was suddenly shattered by the frantic voice of the broadcaster. “Ανακοινωσεις! Οι Τούρκοι έφτασαν στην Κύπρο! (Attention! The Turks have arrived in Cyprus).”

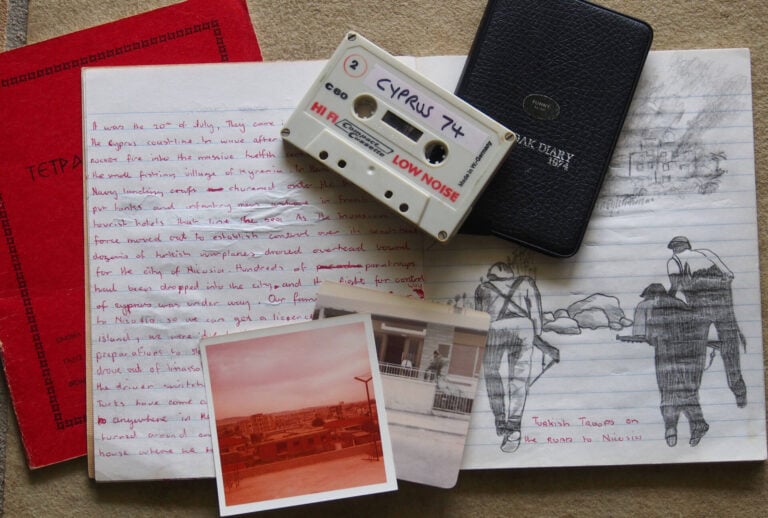

THE TURKISH INVASION

At sunrise on the morning of the 20 July, 1974, my family set off from Limassol by taxi to go to the airport in Nicosia in the hope of catching a flight out of Cyprus so we can return to Australia. On the way to the airport, our taxi driver turned on the his car radio and we heard the shocking news that Turkish troops had landed near Kyrenia.

‘We have to go back,’ said the taxi driver as he proceeded to make a u-turn. ‘We have to go back to Limassol.”

My recollections of what happened next are rather murky. I remember my mother and sisters started to cry. I remember the taxi driver swearing under his breath. I remember my father muttering something and telling everyone to calm down. I remember one of my sisters shouting something like ‘we are going to die!’ and someone else telling her to ‘shut up’.

Within 40 minutes, our taxi had returned to Limassol and the driver dropped us off at Spirou Stathopoulou Street where my Uncle Andrew and Aunt Augusta lived with their young daughter Chrysoula. “They’ve bombed the airport,” my auntie shrieked as she embraced my mother. “We thought you were there and feared the worst.” I looked at my sisters in horror. “Jesus!’ I said. “Imagine if we had left last night and slept at the airport like dad had suggested.”

We sat together and listened to the radio. Reports were coming in about a convoy of tanks on the road between Kyrenia and Nicosia. My heart was beating fast. This was real. This was really happening. I had never seen my parents so distraught and so terrified. My mother’s wailing elevated my own anxiety and fear. At least when I was living on London Street, I could run out onto the street to visit my friends and for a while, be shielded from my mother’s crying and doomsday prophecies.

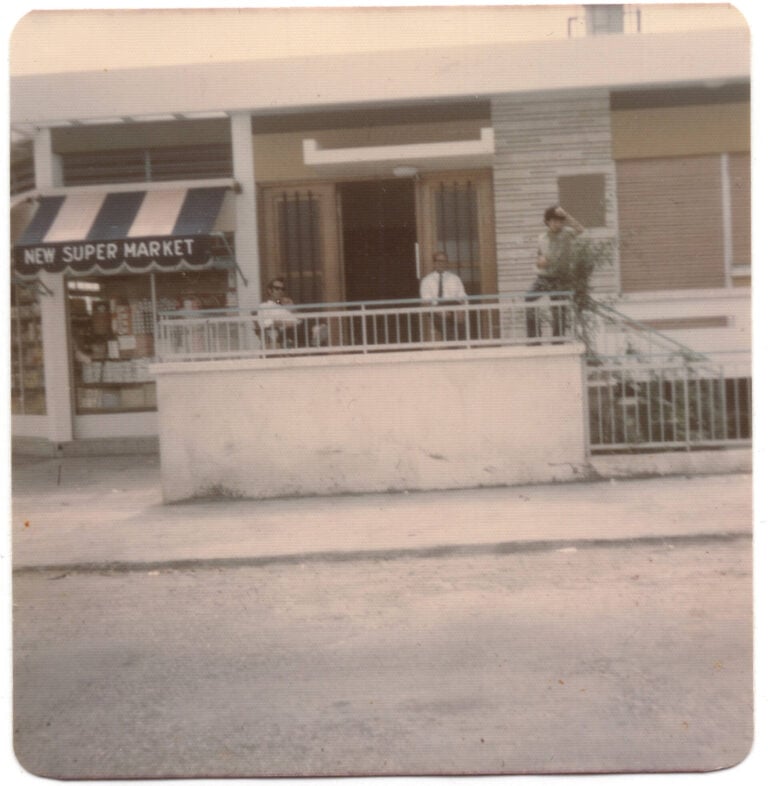

As the sun rose that morning in Limassol a small crowd had gathered outside my Uncle Andrew’s grocery store. As soon as my uncle opened the doors to his shop dozens of people rushed in and began purchasing food and supplies. By the time the store at midday, most of the shelves were empty.

After lunch, I went up to the roof of the house with my uncle and father to scan the horizon. From our third-storey perch we could see fires burning in the distance. Gunfire and explosions could also be heard. Down on the street below we saw around twenty army trucks full of young boys and men of all ages drive past. My uncle told me that all males aged between 18 and 40 were required to go and fight and try and defend Cyprus.

At about 3pm, a man came to visit the house. I’m not sure who he was but he told us that the Turkish army had met little or no resistance and was advancing steadily towards Nicosia and possibly Limassol. He warned us to pack some clothes and head for the mountains.

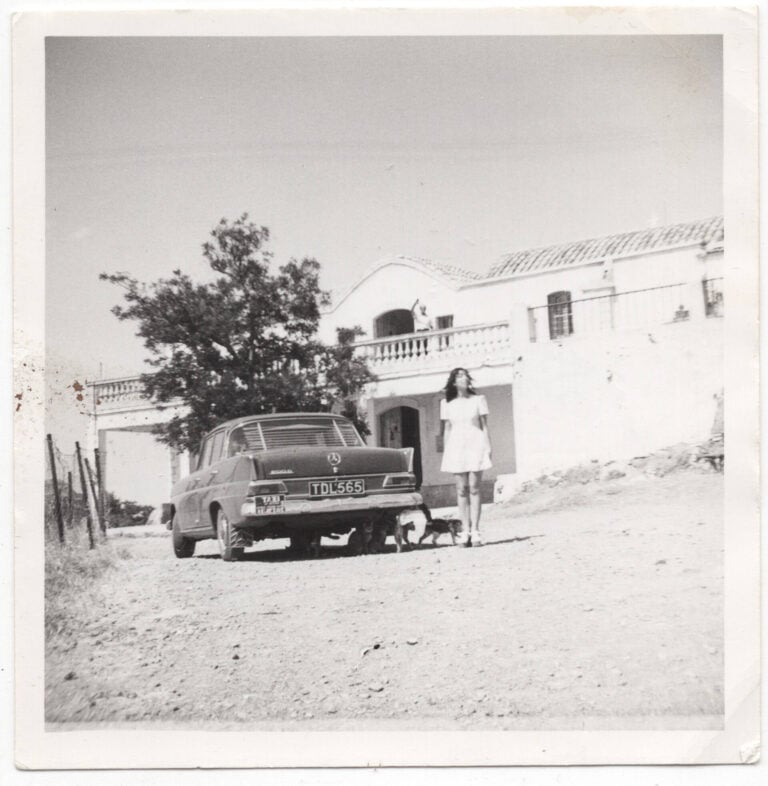

Within an hour we jumped into my uncle’s car (not sure how we did it) and heading for his village of Agios Theodoros. Despite the fact there were nine occupants cramped together in that car – we sat in eerie silence listening to the dreadful news bulletins coming out of the car radio. Along the dusty dirt roads, we saw hundreds of soldiers driving in the opposite direction towards Limassol.

When we reached the village, I was shocked to see how crowded it was. Obviously, others had the same idea to seek sanctuary in the mountains. We stopped our car outside an old two-storey mudbrick house near the centre of the village. The house belonged to my uncle’s parents. Once we had unpacked our bags (with just a few essential belongings) we sat together an ate a simple dinner consisting of bread, cheese and olives. No one had an appetite for anything more.

After dinner, my father and uncle took off to the ‘plateia’ (village square) to visit the kafenia (coffee houses) to try and find any credible news about the situation. The rest of us went to church (Agios Georgios).

As the sun was setting, more and more people came down to the church. There were so many people it reminded me of Greek Easter. We lit our candles, kissed the icons and prayed. After a while, we all came home except for my mother who wanted to stay and pray in the church all night. It was to be expected I guess.

As we walked back to the mudbrick house I noticed how blood red the sky was. It wasn’t just the sunset. The entire sky was red. A smoky red. Someone had mentioned that the sky was red because of all the bombs that had been dropped in the last twelve hours and because of all the fires raging in the mountains near Nicosia.

When my father and uncle returned from the kafenion they said that the situation in Cyprus was very dire indeed and that the whole island was now at risk. They had heard that the Greek Cypriots were vastly outnumbered and did not have any weapons to stage an offensive against the invading forces. As my uncle put it, ‘we are all sitting ducks’.

My anxiety continued to climb that night, as the voice on the radio kept broadcasting report after report of massacres, torture and killings. No doubt some reports may have been exaggerated but I was still terrified.

Things did not improve for me after my uncle announced that we had to cohabitate in total darkness and we were not allowed to switch on any lights or use any candles. In fact, a total ‘blackout’ was imposed on Cyprus for fear of aerial bombing during the night. To further aggravate my fear, I was told to sleep on the balcony with the menfolk as there was no more room inside the house.

As I laid on my back, on the creaky wooden floor of the balcony, staring up at the deep red sky above, I wondered what fresh horrors the next day will bring. Surprisingly, the village was quite at night. The fighter jets that had whizzed through the skies during the day were now grounded for the time being. I wondered how my mother was coping, praying all night in the church down below.

I was awoken the next morning by the sound of church bells. It was Sunday the 21st July. The sky above was still red. It took me a few moments to focus and regain my senses. The deafening roar of a fighter jet screeching across the sky soon shook me out of my slumber. I jumped up and noticed I was alone on the balcony. I yawned and went inside the house. It felt as though I hadn’t slept much at all. My entire body ached.

Everyone was sitting around the table having breakfast. “You gave us a scare last night,” my uncle said as I sat next to him. ‘Is he talking to me?’ I thought. I looked up at him and said, “What do you mean?” My Uncle Andrew then proceeded to tell me that during the night he woke and saw me attempting to climb over the balcony railing. Apparently, he reached out and grabbed me just in time.

I was shocked by what my uncle was telling me. ‘Was I sleep walking?’ I had no recollection of waking up or attempting to climb over the railings on the balcony. My uncle was adamant that this did occur. I asked my father if he saw anything but he just shrugged his shoulders and said ‘he was asleep’.

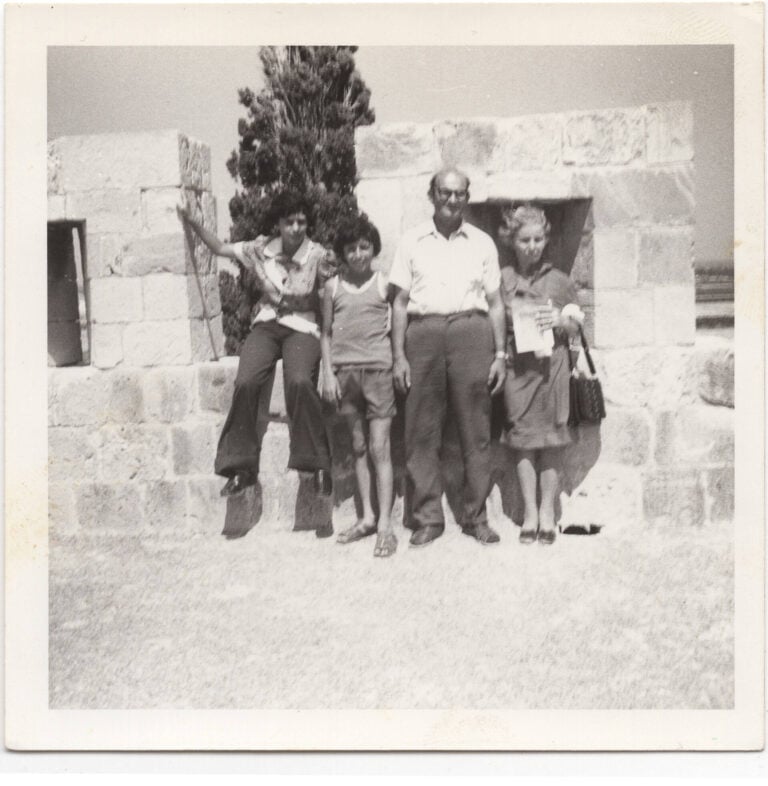

Since it was Sunday, we all went to church dressed in the same clothes we had been wearing all weekend. Understandably, the church was overcrowded again and many people had to wait outside. My mother looked tired but came home with us briefly to have something to eat. She went back to the church later that afternoon.

All day, the tiny radio in our house was reporting grim news. ‘We are all doomed,’ I heard my sister say.

By mid-afternoon, the fighter jets resumed their sorties across the red Cypriot sky. Everything seemed so surreal.

The next day, (Monday 22nd July) my uncle decided to take my sisters and I out into the fields to collect hazelnuts. We even managed to wash our feet in a small stream. I had noted in my diary that it had been five days since my last shower. My uncle was trying to be upbeat and happy but I could tell he was deeply worried. In any case, picking hazelnuts was a pleasant and much-needed distraction for us all.

That night we all went back to church to pray. Once again, my mother chose to stay overnight together with perhaps fifty other women. Once again, I slept on the balcony with the men folk.

Thankfully, there was no mention of any sleepwalking the next morning. Instead, my father and I drove back to Limassol with my Uncle Andrew to pick up some much-needed supplies and fresh clothes from his house. I noticed that the roads were relatively empty and there was a noticeable absence of soldiers and military vehicles.

When we arrived in Limassol all the roads were empty, the shops were closed and there was a pungent smell in the air. The smell of war.

I can’t quite recall how many days we all stayed in Agios Theodoros. I do remember that in late July, my parents decided it was time to try and contact the Australian Police in Limassol to see if they could help us evacuate from the island. After all, we still had our Australian passports.

On a rather hot Summer’s day we all piled into my uncle’s car and drove back to Limassol.

I remember that my father and older sister Helen went to visit the Australian Police Headquarters while the rest of us waited at my Uncle Andrew’s house.

A few hours later my father and sister returned and rather excitedly told us to quickly pack our suitcases. After a flurry of goodbyes, my family and six suitcases were squeezed into my uncle’s car and he drove us to the Australian Police Headquarters. Once we arrived, the Australian Police (God bless them) were waiting for us with a Datsun and a Land Rover. Both cars had their engines running.

My mother, father and sisters Toula and Helen sat in the Datsun while my sister Ann and I climbed into the Land Rover. Unfortunately, there was not enough room for our six suitcases and so two had to be left behind; mine and my mothers. I was devastated. So many keepsakes and personal items left behind.

We drove at a great pace to the British Air Base at Akrotiri. Once we arrived we were provided with refreshments and a few sandwiches. We had to wait inside the small airport for around twelve hours.

At around midnight we were finally allowed to board a large Hercules military transport plane. I remember at the airport I felt the urge to go to the toilet but chose to wait until I boarded the plane. That was a grave mistake and a decision I would regret throughout the eight-hour flight to England. There is no need to give you the details only to say I had never felt such stomach pains in all my life.

I can’t tell you the relief I felt once our plane landed in Sussex, England. Relief that I could finally go to the toilet and relief that we had arrived safely out of a war zone.

We stayed with relatives in London for two weeks before boarding a plane back to Melbourne, Australia.

I remember my school friends rushing to greet me upon my return to my school. I was even asked to speak at a school assembly and to recount my adventure in Cyprus. ‘Adventure’ was the term the Head Master used. I was content with the word ‘tragedy’.

Soon after my family had returned safely to Australia, my passion for Cyprus intensified. I began to document my experience and memories of the island through my art and written stories. Although, the final part of our trip was horrible and frightening, I had experienced enough wonder and beautiful moments to really appreciate the land and the people.

It would be nine years before I would return back to Cyprus. In 1983, I decided to travel around the world with a school friend capping of my trip with a lengthy stay in Cyprus. I was shocked to see just how much had changed since my first visit, especially in the villages. It seemed to me that the way of life I had witnessed in 1974 was slowing disappearing. I was glad to reconnect with friends in London Street and to revisit so many of my beloved relatives. Everyone agreed that Cyprus had changed forever but they remained hopefully that the island will be reunited and at peace again soon.

Needless to say, my experience in Cyprus in 1974 has had a profound impact on my life and this has been especially evident in my creative pursuits. Perhaps the seed for Tales of Cyprus was actually planted as I was roaming the countryside in 1974 before the coup d’état and the Turkish Invasion changed the fate of the island forever.

I hope to can continue to pay homage to my Cypriot roots for a long time to come.