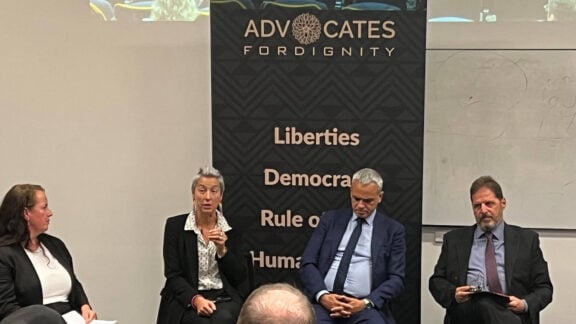

On Monday evening, an esteemed panel of experts on refugees and asylum seekers gathered for an event titled Navigating Displacement and Belonging: Comparative Perspectives on Refugee Integration in Greece and Australia.

The human toll of displacement

The event was hosted by Advocates for Dignity, Victoria, with its head, Abdulcelil Gelim, speaking first to highlight the real human cost of displacement. Gelim pointed to Afghanistan, where “entire generations have grown up with displacement as a ‘normal’.”

He continued: “In Ukraine, over 13 million people have left since 2022, and in Gaza, more than 60,000 people’s lives have been lost, with children bearing the heaviest burden of war.”

“Yemen is the site of one of the world’s most severe humanitarian crises, and it continues with millions uprooted from their homes,” he said.

“The Uyghur people in China suffer mass detentions and cultural erasure on a scale that demands our conscience.”

Gelim also spoke of Turkey, his original homeland, where “politicians, teachers, and journalists” are being jailed for criticising Erdogan’s government, and many are fleeing.

Europe’s frontline and the many challenges

The panel included two leading Greek scholars, Professor Sotirios S. Livas of the Ionian University in Corfu and Associate Professor Emmanuel (Manos) Karagiannis from King’s College London, both experts on migration, the Middle East, Islam, and democracy. They offered insights into the challenges facing Europe’s migration frontline, Greece. The Australian panellist was Jana Favero, Deputy CEO of the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (ASRC), founded by CEO Kon Karapanagiotidis.

Favero opened with a pointed critique of the Australian government’s plan to deport asylum seekers to Nauru. She said that while Australia has a good refugee and migration policy, asylum seekers coming to Australia outside the legitimate process suffer great indignation and have no rights.

“Everyone is welcome in our country at the same time as they’re paying half a billion dollars to send people offshore to deport them and make it almost impossible for that to be challenged,” Favero said.

“I find it very hard to believe it’s a Labor government doing this,” she added.

She said under the new rules anyone here even for up to 10 years can be deported to Nauru and has no recourse.

“If it sounds like America, and ICE, it’s because it is, and we know that other countries follow what we do. We started offshore processing, and other countries have copied us – it’s really setting a dangerous precedent.”

Professor Livas highlighted the global climate crisis as a key driver of displacement. Southern European front-line states like Greece, Italy, and Spain face asylum seekers not only from conflicts following the 2011 Arab Spring but also from climate change, which has left much of Sub-Saharan Africa and the Maghreb without water.

“Following the Arab Spring, there were many civil wars and conflicts. As a result, Libya doesn’t exist anymore, Syria doesn’t exist anymore. There are certain countries that exist only on the map,” Livas said.

He described a “fragmentation of identities” and asked: “What does it mean to be Libyan today? What does it mean to be a Syrian today? What does it mean to be a Yemeni today?”

Added to conflicts, the global climate crisis forces people to leave “in search of a better life.”

He noted that there is little the EU, U.S., or UN can do to change conditions in countries facing conflict and environmental disaster.

“How would they interfere in Sudan, one of the bloodiest conflicts in the world, where 300,000 people have been killed? We have six or seven million refugees. So, what can we do about it?”

Livas argued that Western states, particularly the EU, need to be pragmatic. “We need to accept something that, morally speaking, is difficult to accept, but we need to accept that there will be more conflicts that we cannot stop.”

He called for a unified EU response, noting that northern Mediterranean states – Spain, Italy, and Greece – “have received hundreds of thousands of refugees.”

“There is so much confusion about the refugees in Europe and the world. Most people do not understand that the refugees are not migrants.”

He added that media and populist politicisation has led people to think refugees “have nothing else to do in their lives than to take a boat, you know, to start this risky journey because they want to claim EU benefits.”

“People do not understand that, first of all, there is a legal obligation to protect refugees. This is what is supposed to define Europe.”

Politicisation, insecurity, and a call for empathy

Associate Professor Karagiannis emphasised the politicisation of language around refugees.

“Twenty years ago, we didn’t talk about the issue of security. We talked about the human dimension; the legal language had an international dimension, and we didn’t talk about security.”

“The extreme right policies now in Europe have to do with our inability to deal with social and economic crises in the countries of Europe and the South.”

He added that while we speak of “post-crisis Greece, Greece is still in crisis,” economic insecurity drives the scapegoating of refugees.

“All this has to do with the insecurity governing our lives,” Karagiannis said, calling for telling human stories, not just numbers.

He highlighted that 1,200 people have drowned in the Mediterranean trying to reach Greece, Italy, and Spain.

“People just read numbers, but behind these numbers are human stories – stories of people who are forced to leave, families torn apart. You must know that there are 1,200 stories of families and people.”

The event concluded with Livas and Karagiannis noting that ordinary citizens should not be blamed for the refugee crisis; rather, politicians who fail to explain the reality to the public are responsible. Livas stressed that solutions must be European, not solely Greek, Italian, or Spanish. He pointed to Hungary, which has no sea borders and has hermetically sealed itself against refugees.

“In the end, many of these refugees do not want to stay in Greece; they want to go to Sweden and Germany, where they have family.”

The discussion left attendees with a clear understanding that addressing displacement requires not only policy change but empathy and a shared commitment across nations. The audience included key community and political leaders such as former commonwealth Labor MP, Maria Vamvakinou, and one of the leaders of Cultural Pulso Nick Hatzoglou.