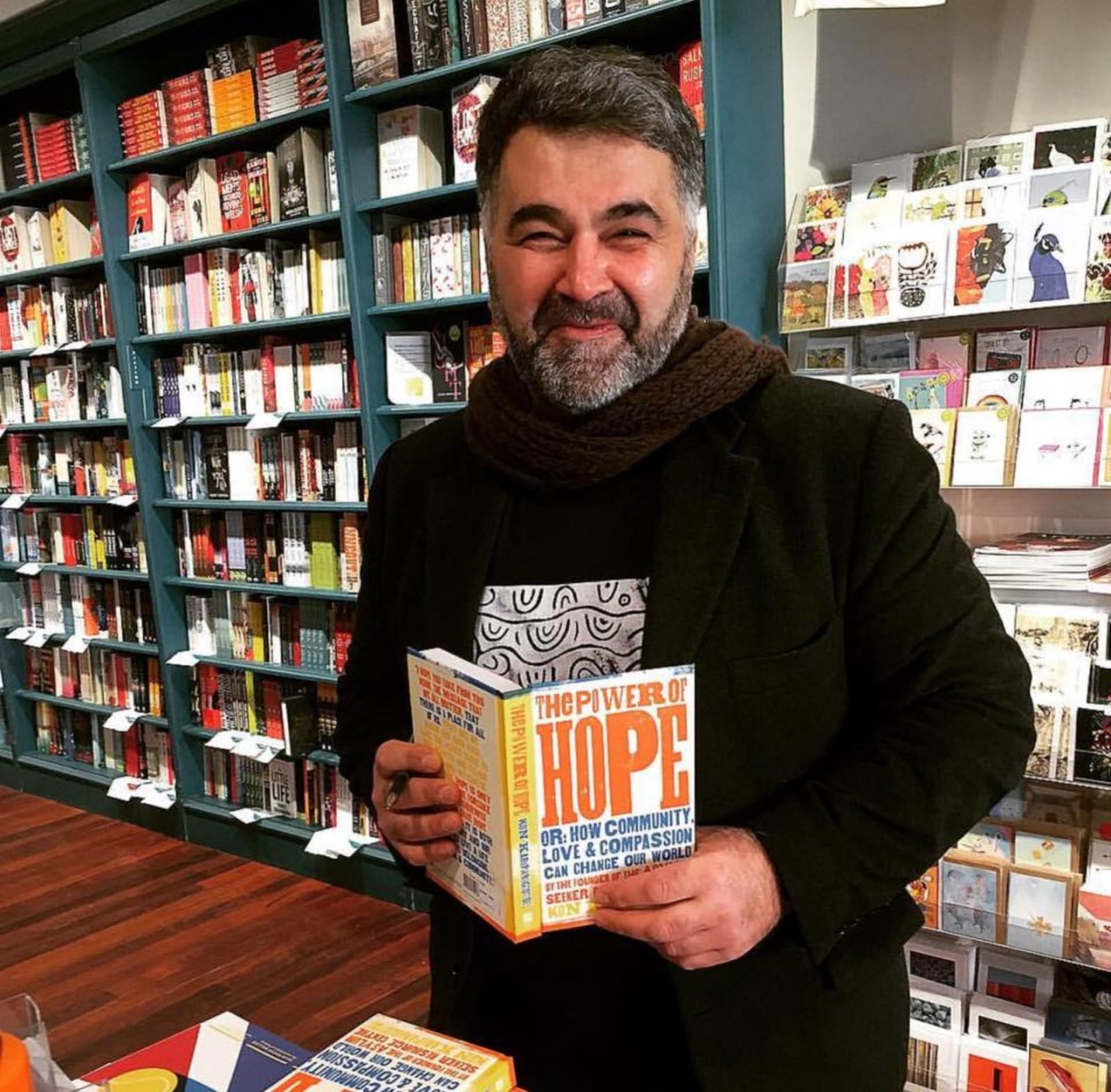

Kon Karapanagiotidis OAM is tired. He’s suffering a throat infection and has just returned from ten-day national book tour for The Power of Hope or: How Community Love and Compassion can change the World.

“Yiasou mate… I’m running ragged… they’ve worn me out again,” he rasps over the phone.

Kon has decided to carry much on his shoulders as the Founder and CEO of the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (ASRC). He is a human rights lawyer, social worker, philanthropist, masseur and lay chef.

“I never thought of writing a book, when Harper Collins approached me last year to write a book about hope, I was going through hard times, life was tough, but that was what inspired me, because I thought all refugees and migrants struggle for hope,” Kon says.

Kon has built a fiefdom of virtue. The Centre’s lifeblood is made of volunteers – many are refugees and migrants. Philanthropy, fundraising and income-generation, through projects and services, add to the Centre’s coffers for the very necessary work.

“The people I work for struggle on a daily basis – refugees, asylum seekers, and all of us struggle, regardless of who we are.”

His struggle is for those asylum seekers that suffer Kafkaesque horrors in Australia’s offshore detention camps; for asylum seekers on temporary visas, who’ve just been cut off from the meagre $35 a day support that Status Resolution Support Services (SRSS) provided up until June this year.

These refugee fathers and mothers echo what our own Greek, or Italian, parents said to us: ‘We came here for you, we sacrificed for you.’ They suffer the indignation of racism and when they’re home they keep reminding themselves of why they are here. Kon says, “My parents never wanted to leave their home, no migrant or refugee wants to leave home and we all need to remember that.”

A photo taken at the opening of the ASRC 17 years ago.

Kon and the ASRC volunteers celebrate the outcome of the recent fundraising telethon.

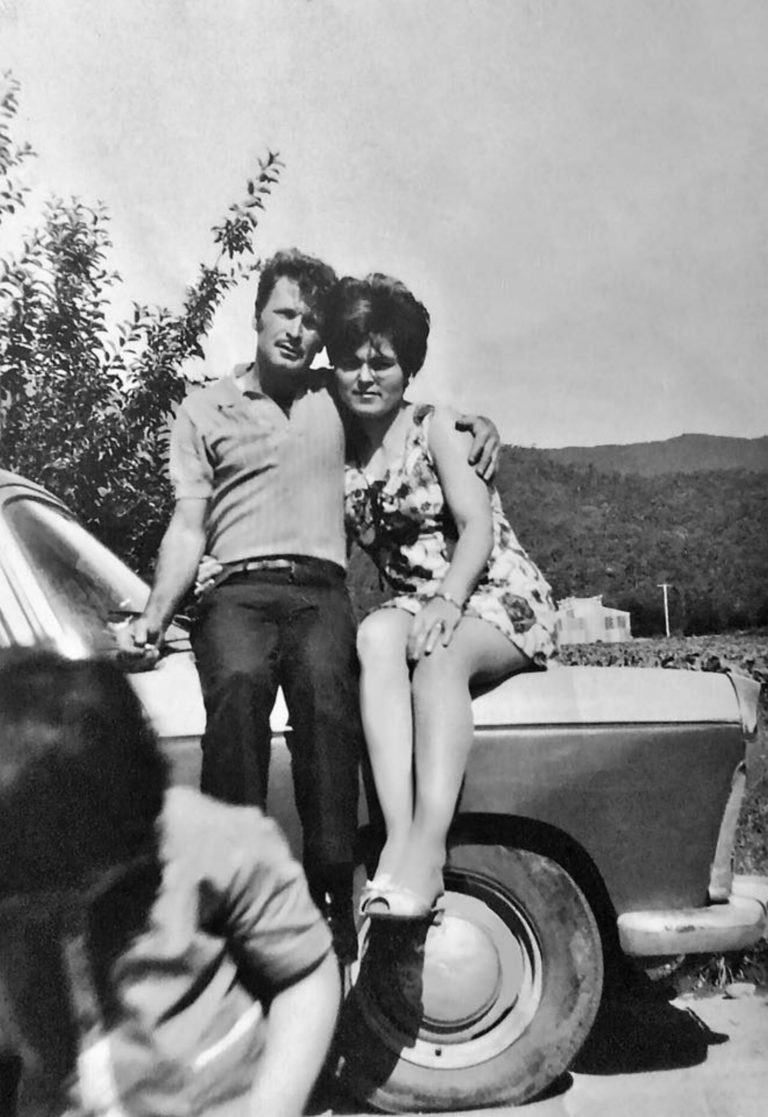

A TRIBUTE TO PARENTS WHO SACRIFICED EVERYTHING

Kon’s book is a mirror to us, children of migrants. It begins with a hagiography of his grandmother Parthena, one of the hundreds of thousands Pontian Greeks who suffered in the Genocide sanctioned by the Ottoman Empire in 1923.

He writes about his father and mother who “sacrificed everything for Nola [Kon’s sister] and me, working as labourers on farms and factories until their bodies could no longer take it. They worked hard for more than forty years so that their children could dream of something better.”

“I wanted to honour my father in this book and my mother, they survived in spite of the racism and all that we are, my sister Nola and I, is because of them,” he says.

Kon talks of the reality that “we” children of migrants, “have to be exceptional and our resilience and our unbreakable spirit is because of our parents”.

Reading his book tore scabs off my own wounds I thought had healed. Wounds that I hope my son won’t carry.

Kon’s father, like mine, died in his early 60s. Like many of our fathers, they were both broken. Broken by war and exile. Our parents survived the horror of the Nazis. They saw their people descend into the fratricide of the Greek Civil War, after the Nazis left.

Regardless of our parents’ divergent class backgrounds – his working-class, mine petty bourgeoisie – they were humiliated by bigotry, menial jobs, isolation and poverty.

Both his mother and father had what Kon describes in his book as “an unforgiving childhood.” Forced to leave school at an early age and growing up in poverty, they both worked in the tobacco farms in regional Victoria and in factories in Melbourne.

“They were treated like shit on the tobacco farm and later my father was treated with contempt by his boss and peers in Collingwood in a wool dye factory,” says Kon.

“It was casual racism by the boss and workers, they assumed my dad was a peasant and stupid.

“They’d laugh at my father in front of me, and my mother also used to suffer daily humiliation,” he adds.

Yet these parents raised a son with an OAM and a daughter who share “eight degrees” between them. “That is what migration and struggle create,” he says.

In his book, he talks of his father looking like James Dean, a good looking man – in a photo of him bear-chested in the country, he looks more like Martin Sheen from Apocalypse Now. His mother Sia was a “force of nature” who loved him and “yet at the same time created so many issues” for him.

His parents’ anger often unleashed chaos and Kon was forced to become the ’emotionally mature’ teen that reconciled them. Love is not enough when your bones and psyche are shattered.

A STRUGGLE FOR MIGRANT MEN TO FIND IDENTITY

Kon is also concerned about men and violence. I ask how he can on the one hand run the narrative of ‘male toxicity’ and deal with refugee and migrant men, who have been emasculated and many of their traditional values have been challenged in Australia.

“I love men, not all men that are violent or bad, but men have choices not to be violent, and there is a struggle for migrant men to find identity and power, if they feel they have been emasculated,” Kon says.

“I ask myself why are men killing themselves at such a rate? What is it that makes many unable to express vulnerability? I look at my father, and the Greek men I grew up with,” he adds.

“Like Greek men from that time, my father was stoic, with a Greek maleness, born in the shadows of trauma, yet he was humble, loving and warm,” Kon’s voice breaks. We talk of dead fathers.

Kon empties himself out in his book. It’s agonising, gripping and stirring. He talks of his struggle with his body image, with isolation, with racism. He also talks of his tenacity to reclaim his narrative. He ran marathons; he travelled to Europe, Asia and the US. He talks of the emotions that overwhelmed him when he visited a former-Nazi death camp. One sees how his own life, his work, turned turn anger into a beam of light.

Photos from Kon Karapanagiotidis on his recent book tour.

We talk of the racism now that has been expressed towards Africans and Muslims especially by some in our own communities. How can we who claim Aristotle’s legacy, his search for ‘good’, or even the Christian message of love, be wary of new immigrants and refugees?

“It maybe self-loathing, the desire to be accepted in the mainstream, many in our immigrant communities desire validation,” Kon says.

“We need to be reminded that we – Greeks and Italians – may not cop the same level of abuse as Africans, or Muslims do, but we did once, and we still suffer bigotry.

“You have felt aggressions, assumptions, stereotypes, accepted all the jokes, the stuff we’ve taken in for years and made us resilient and some of us self-loathing” Kon says. I have, we have and still do.

“I always say in my talks, everyone here other than the Aboriginal People are migrants or refugees, be they from England, Ireland, Poland, Greece, China or anywhere,” he adds.

Kon regularly sites Dr Martin Luther King Jr. as his inspiration. However he seems more like the Martin Luther, the German radical monk-activist. Kon in The Power of Hope begins his search in torment and grief, burdened with physical, emotional and intellectual pain, not unlike Luther. And, like Luther’s Ninety-five Theses, Kon has built the ASRC as a beacon for hope. We both agree in the end that, for all the transgressions we suffered and others suffer now, there were always those that welcomed us.

* ‘The Power of Hope or: How Community Love and Compassion can change the World’ is out from Harper Collins Australia.