The terror of the war has kept his eyes teary for years now. The atrocities he witnessed 45 years ago now torture his mind. Nightmares covered in blood and dust kept him awake every night for more than 10 years after the war.

“They still come to haunt me some nights. Less often now,” says Dionisis Daskalou, from his Melbourne home.

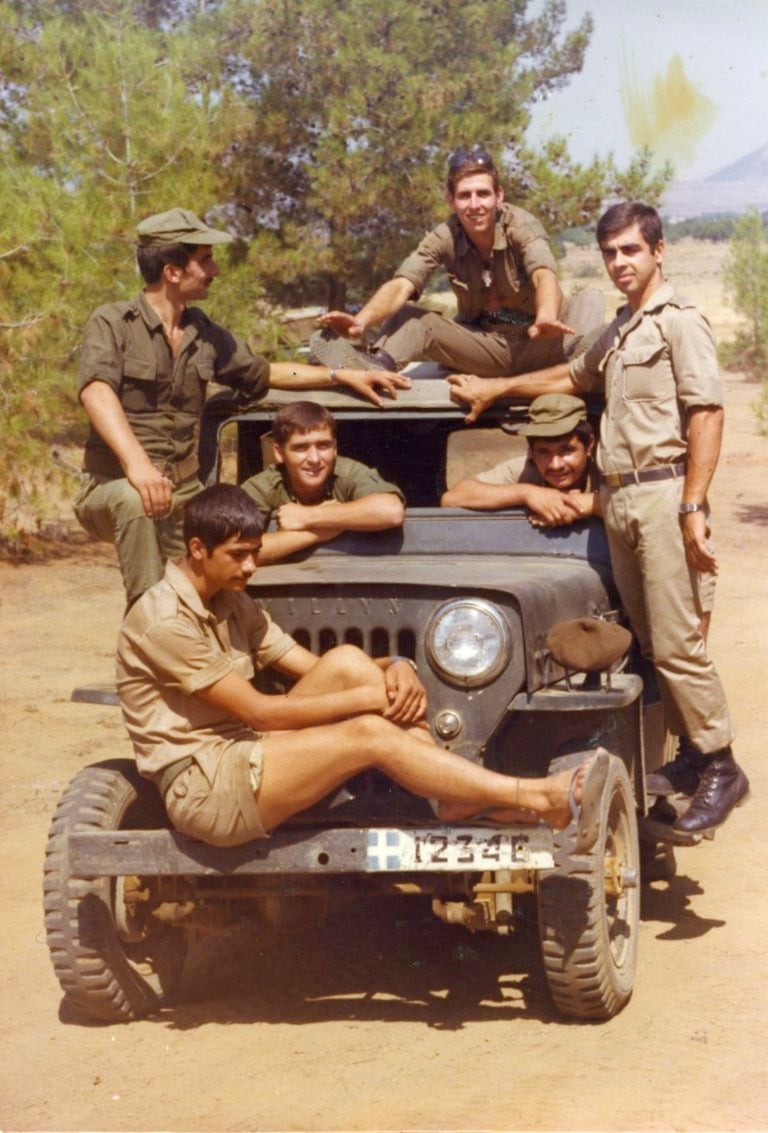

Apart from the invisible trauma of the war, Dionisis carries an even more painful wound. It is the stigma of the ‘χουντικό’, the traitor. He was one of the soldiers of the Hellenic Military Force in Cyprus (ΕΛΔΥΚ) during those dark times of betrayal on the island in July and August 1974. Dionisis was not one of the high-up army personnel. Those were giving orders and worked for the Greek junta, hence their later promotions to the upper echelons of the Greek Army Force. He was just a soldier, trained as a driver. He was one of those who saw the first bombing of Cyprus from the Turkish air force, who bore the brunt of the brutal attack of the enemy, who witnessed the mutilated bodies of his fellow soldiers. No, Dionisis didn’t give orders. He followed them, even if he couldn’t understand why when the men of ‘ΕΛΔΥΚ’ were advancing and inflicting pain on the Turkish troops, suddenly their commanders ordered them to retreat.

With sorrow and despair deeply engraved on his face he narrates his story.

“The junta didn’t betray just the people of Cyprus, they betrayed us too. We are the victims not the traitors. For more than 20 years the Greek government didn’t recognise our contribution. Many brutally wounded and permanently damaged fellow soldiers who fought in Cyprus during the war received a petty pension and the Greek state was issuing them IDs stating that they had fought in WWII. So what happened in Cyprus? Wasn’t that a war? What did we do there? And it is not that they didn’t respect us; they didn’t show any respect to our parents either. There are still missing soldiers, mothers are still waiting for their sons. I remember that aeroplane that was gunned down by friendly fire. I saw it. Our own side went afterwards with a bulldozer and covered everything, wreckage and bodies. I was at the 2nd garrison and I saw it,” he says, referring to ‘Niki 4’ the plane that carried Greek marines to Cyprus and was shot down by friendly fire on the dawn of July 22, 1974 due to the delay of the Hellenic Armed Forces Headquarters to alert the Cyprus National Guard of the arrival of the planes bringing help.

The political and military elite at the time, protagonists and perpetrators of the Cypriot tragedy, were never charged and tried for abandoning Cyprus to blood thirsty Turkey, with the tolerance, of course, of the great powers. Besides, for the Greek state, as Dionisis rightly points out, there was no war in Cyprus. After all, the word ‘Cyprus’ was added to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Sintagma just a few years ago.

“We were all branded traitors and fascists. How can I be a fascist? My uncle was an antarti killed in the Battle of Edessa. My grandfather was exiled in Makronissos for six years. Traitors do not fight on the battlefront, traitors are cowards. ΕΛΔΥΚ’s boys fought like heroes,” he adds.

For the 1974 events in Cyprus, Kostas Karamanlis’ government in Greece decided in March 1975 to suspend prosecutions for the crimes committed by the junta clique against Cyprus. As Karamanlis put it, prosecutions of those responsible for the coop and what followed in Cyprus “may disrupt the international relations of the State”. Even if no amnesty was formally given to those traitors, there was an indefinite postponement for their prosecution.

Due to impunity and collective ignorance, to which the archives – classed as classified for many years (Cyprus Secret Files) – have contributed; the main culprits of the Cypriot tragedy presented themselves as victims of a supposedly dark plot and various conspiracy theories. The real victims of this criminal silence are the soldiers of the Hellenic Military Force who fought in Cyprus. There were hundreds of soldiers and officers of ‘ΕΛΔΥΚ’ who fought with heroism and self-sacrifice, trying to ward off the Turkish invasion. Dionisis was one of them.

WAR HAS DAWNED

Dionisis arrived in Cyprus on 19 July, 1974.

“We went from Greece to make the change. Arriving in Ammohostos and coming out of the ship we saw a castle with mounted guns. They were Turks. We stumbled with that. Soon we were told that there is nothing to worry about as that region was Turkish. In the afternoon they transferred us to ‘ΕΛΔΥΚ’s’ army camp telling us to sleep with our clothes that night because there were fears that the eruption of a war was imminent. We didn’t take it seriously. We thought that they were trying to give us a scare, as it was our first day in Cyprus, a common practice of the older soldiers to the newcomers.”

READ MORE: Cyprus timeline of a crisis: 45 years of heartbreak

The next morning Dionisis woke up, and went to have his breakfast. The vividness of his description of what happened that day, the pauses in his narration and the tears that escape on his chicks while talking, a grim realisation that this man is reliving the fear and the brutality of 20 July, 1974.

“I took my breakfast and headed towards the tracks. Suddenly I see the first Turkish plane. It looked like a huge flying barrel coming towards me. In a split second, the first bomb hits the command’s building. The bomb flew about 10 meters above my head. Terror grabbed me by the stomach, twisted it and paralysed me. It wasn’t a lie. War was happening. A cloud of dust covered everything, objects were falling from the air, I could not trust my eyes. I pulled all the strength remaining in my body and I started moving west, trying to find a place to protect myself. Another bomb hits a toll close by. The barrack blew up with millions of shrapnel fragments falling from the sky. I saw one soldier dead and another boy had lost his hand from the shoulder. The horror on his face is indescribable. One second he was staring at his hand, jumping and the next his limbless shoulder. I started trembling. I did not stop until a couple of days later. I thought I was losing my mind.” That’s how the war began for Dionisis.

The next day, he was ordered to go to the 2nd garrison. He remembers an encounter on his way there with a fellow soldier who was born in Edessa like himself. Theodoros Charalambides is missing to this day.

“Speaking to him brought back some sense of normality. He talked about his mission, adding that if did not drop 10 Turkish planes, he would kill himself. He was an average height guy, but in my eyes that minute he looked like a giant. He was a courageous boy that’s why he stayed in the army camp during the second invasion and he is still a missing person. With us was Marios Tokas too, was he a traitor as well?” he asks proving that the stigma about him and his fellow soldiers being traitors is the most painful wound of that war; it aches to this day.

After his post to the 2nd garrison, Dionisis ended at Gerolakos. He was there when the second invasion of Cyprus happened.

He remembers what he saw and heard about one of the most heroic battles in Greece’s modern military history, the epic battle at “ΕΛΔΥΚ’s” camp. It was one of the most unequal battles. It lasted for three days.

“For 60 hours the 318 heroes of ΕΛΔΥΚ fought 7,000 Turkish and Turkish Cypriot soldiers. The battle was taking place with 38 degrees heat and our soldiers fought shirtless. When the Turks entered the camp, our children battled body to body. On the second day the commander asked for help. Nothing came through. The third day our boys started to make inroads with the Turks, then suddenly the field artillery takes the order to leave. They said they had no ammunition left. How do you fight tanks with M1s? Some boys despaired, threw their arms up and waited for the end. Some marines arrived and helped them somewhat, but they were also ordered after a while to leave.”

READ MORE: Cyprus protests in Melbourne call for justice 45 years since Turkey’s invasion

Within the ΕΛΔΥΚ camp, the Turks committed indescribable atrocities. They beheaded 10 bodies of ΕΛΔΥΚ’s dead, and placed their heads on the pavement at the entrance of the camp. Then they took turns photographing themselves with the beheaded victims.

“The Battle of ELDYK is taught at the British Military Academy today. About 90 of our boys were killed. But Nicosia was saved,” Dionisis adds proudly.

He stayed in Cyprus for 18 months in total.

“In 1978, with some other fellow soldiers, we created a club and went to see Averoff, the then Defence Minister of Greece. Do you know how he treated us? He asked us to dissolve the club and baptised us fascists, right wing radicals. Who? The one who is the definition of far-right ideology told us that. They wanted to cover up their own mistakes using us,” he concludes with bitterness and disappointment.

Dionisis for years chose not to talk about his experience during those dark days in Cyprus. He does not want to forget though. His tablet is full of YouTube videos of testimonies.

“I watch them very often. I am trying to make some sense of it all. I try hard. I decided to talk now because we will die and all will be forgotten. No one was brought to justice for what they have done to us.”

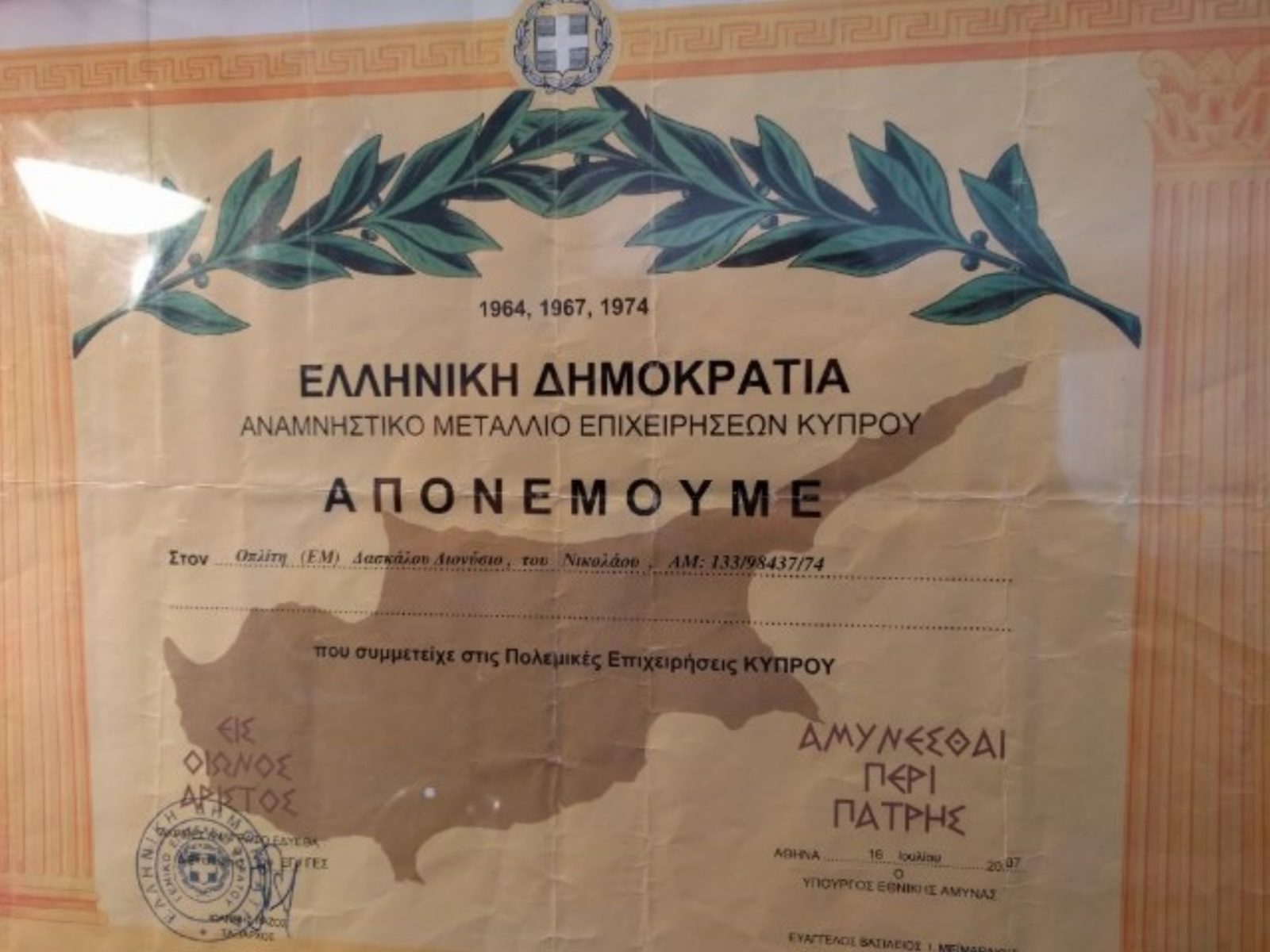

A few years ago, the Republic of Cyprus recognised the ΕΛΔΥΚ soldiers with special medals. Something similar was done by the Greek state.

“Two little too late for us and nothing for the mothers and fathers who still await the bodies of their children to rest them in peace,” Dionisis concludes.

READ MORE: Graffiti in Cyprus paints a rich and complex picture of this divided society

Dionisis today, reading through a book dedicated to the experience of him and other Greek soldiers of ΕΛΔΥΚ.

A certificate of recognition from the Greek State.