Ekpyrosis (ἐκπύρωσις), the ancient Greek term for conflagration, describes a Stoic belief in the periodic destruction of the cosmos by a great conflagration every Great Year – according to Plato, every 36,000 years.

After the ekpyrosis, the cosmos would then be recreated, (palingenisis or παλιγγενεσία) only to be destroyed again at the end of the new cycle. In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus is quoted in Greek using the same word, “παλιγγενεσία” (palingenesia) to describe the Last Judgment, foreshadowing the event of the regeneration of a new world. Of course, preceding this would be a general conflagration.

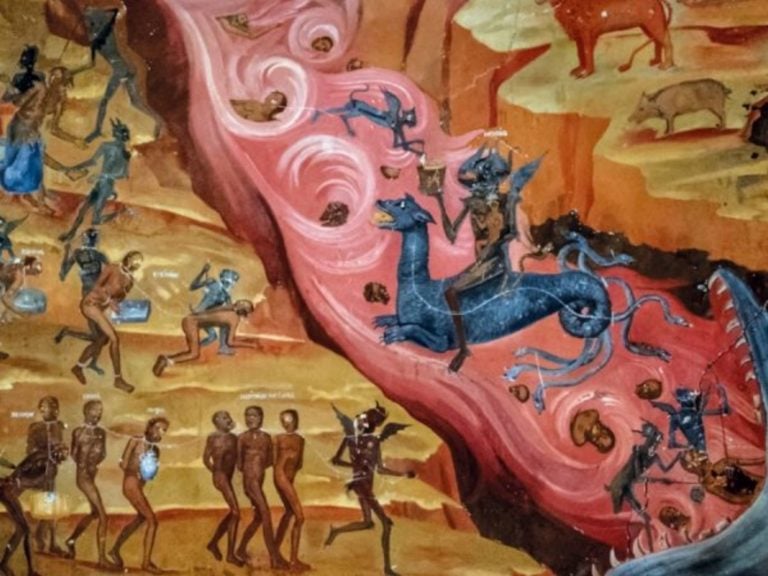

The last book of the Bible, the Revelations, describes the stages in which fire is expected to destroy the world:

Upon the sounding of the first trumpet, hail and fire mingled with blood is to be thrown to Earth, burning up a third of the trees on the planet, and all green grass. Upon the sounding of the second trumpet, something described as “a great mountain burning with fire” plunges into the sea and turns a third of the oceans to blood. Soon after, a third of all sea life and a third of all ships are expected to be destroyed. At the sounding of the sixth trumpet, horses will be unleashed, exuding plagues of fire, smoke, and brimstone from their mouths, which are said to kill a third of mankind. fire. Fire is also at the end of all these trials and tribulations: When the Last Judgments takes place, the wicked, along with Death and Hades, are cast into the Lake of Fire and the world is made anew. Fire, therefore, has been an eschatological element of wrath since the time of Sodom and Gomorrah.

The unprecedented magnitude and intensity of the fires blazing in New South Wales, Victoria and other parts of Australia, coupled with the recent Siberian and Amazonian conflagrations, has seen these assume apocalyptic proportions in the minds of many. As vast amounts of the country burn, millions of animals perish, lives and property is lost, there is that part of our psyche that links this calamity to our own hubris, that of our civilisation, our culture and our way of life. Many cannot help thinking that like Icarus, or Phaethon, the hapless son of Helios, the sun, who stole his father’s fire chariot and in his arrogance, ended up burning the planet, that we too have flown too close to the sun, and in the process are now destroying ourselves. Others, deny this altogether.

In Plato’s Timaeus, the story of Phaethon precedes that of Atlantis, and Plato ascribes the myth to an explanation of period conflagrations that occur in a cyclical nature. There is no human agency there. Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomeos on the other hand, is quite clear in detecting a human hand in environmental degradation, one that leads ultimately to mankind’s own imperilment: :If human beings were to treat one another’s personal property the way they treat the natural environment, we would view that behaviour as anti-social and illegal. We would expect legal sanctions and even compensation. When will we learn that to commit a crime against the natural world is also a sin?”

“The way we respond to the natural environment is directly reflects the way we treat human beings. The willingness to exploit the environment is revealed in the willingness to permit avoidable human suffering. So the survival of the natural environment is also the survival of ourselves. When we will understand that a crime against nature is a crime against ourselves and sin against God?”

READ MORE: Bushfire appeals: Find out how you can help

Accordingly, rather than being innocent victims of elemental forces, or of the cyclical nature of things, Patriarch Bartholomeos clearly identifies human agency as a key contributor to the planet’s destruction, he categorically condemns it. From his perspective, climate change, and its inevitable consequences, arise because we and our governments, do not truly value our environment or our place within it: “We have traditionally regarded sin as being merely what people do to other people. Yet, for human beings to destroy the biological diversity in God’s creation; for human beings to degrade the integrity of the earth by contributing to climate change, by stripping the earth of its natural forests or destroying its wetlands; for human beings to contaminate the earth’s waters, land and air – all of these are sins. We are treating our planet in an inhuman, godless manner precisely because we fail to see it as a gift inherited from above.

Our original sin with regard to the natural environment lies in our refusal to accept the world as a sacrament of communion, as a way of sharing with God and neighbour on a global scale. It is our humble conviction that divine and human meet in the slightest detail contained in the seamless garment of God’s creation, in the last speck of dust.”

Accordingly, we are the authors of our own apocalypse. Nonetheless, Patriarch Bartholomeos points to an understanding of the interconnectedness of all living things with the planet and a broad based empathy as key to surviving and heading off the consequences of our own rapacity.

“It should not be fear of impending disaster with regard to global change that obliges us to change our ways with regard to the natural environment. Rather, it should be a recognition of the cosmic harmony and original beauty that exists in the world. We must learn to make our communities more sensitive and to render our behaviour toward nature more respectful. We must acquire a compassionate heart – what St. Isaac of Syria, a seventh century mystic once called a heart that burns with love for the whole of creation: for humans, for birds and beasts, for all God’s creatures.”

“The fundamental criterion for an ecological ethic is not individualistic or commercial. It is deeply spiritual. For, the root of the environmental crisis lies in human greed and selfishness. What is asked of us is not greater technological skill, but deeper repentance for our wrongful and wasteful ways. What is demanded is a sense of sacrifice, which comes with cost but also brings about fulfilment. Only through such self-denial, through our willingness sometimes to forgo and to say “no” or “enough” will we rediscover our true human place in the universe.”

READ MORE: Open letter: Archbishop Makarios calls for action to help in bushfire appeal

In his view, one thing is certain: the consumerist way of life we have been living since the Industrial Revolution is not underpinned by an ethos that leads to harmonious coexistence with our natural environment. Our whole way of looking at our civilisation needs to be reviewed:

“Ecology cannot inspire respect for nature if it does not express a different worldview from the one that prevails in our culture today, from the one that led us to this ecological impasse in the first place. What is required is an act of repentance, a change in our established ways, a renewed image of ourselves, one another and the world around us within the perspective of the divine design for creation. To achieve this transformation, what is required is nothing less than a radical reversal of our perspectives and practices.”

Conservation, according to Patriarch Bartholomeos, is not a political issue. It is an existential imperative: “We have been commanded to taste of the world’s fruits, not to waste them; we have been commissioned to care for the world, not to waste it. When Christ fed the multitudes with a few loaves and fish on a hill in Palestine, he instructed his disciples to “gather up all of the remaining fragments, so that nothing may be lost.” (John 6.12) This instruction should serve as a model in a time of wasteful consumption, where even the refuse of affluent societies can nourish entire populations….”

“Climate change is much more than an issue of environmental preservation. Insofar as human-induced, it is a profoundly moral and spiritual problem. To persist in our current path of ecological destruction is not only folly. It is suicidal because it jeopardizes the diversity of our planet. Moreover, climate change constitutes a matter of social and economic justice. For, those who will most directly and severely be affected by climate change will be the poorer and more vulnerable nations (what Christian Scriptures refer to as our “neighbour”) as well as the younger and future generations…”

Furthermore, one thing that is forgotten in the whole debate about ecology is what is actually means. This is a point that Patriarch Bartholomeos is quick to make: “The word “ecology” contains the prefix “eco,” which derives from the Greek word oikos, signifying “home” or “dwelling.” How unfortunate, then, and indeed how selfish it is that we have reduced its meaning and restricted its application. This world is indeed our home. Yet it is also the home of everyone, just as it is the home of every animal creature and of every form of life created by God. It is a sign of arrogance to presume that we human beings alone inhabit this world. Moreover, it is a sign of arrogance to imagine that only the present generation enjoys its resources.”

If we are to learn something from our current ekpyrosis, it is this: Just as it is more than likely that we hold the seeds of our own destruction in our hands, so too do we also hold the elements that will ensure our salvation. A palingenesis, that will see human civilisation rise, phoenix-like from the ashes of its own folly, and re-generate, hopefully to avoid the mistakes of before is not merely a pious hope. It is a moral clarion call.

The Greek term μετάνοια, is often translated as repentance. Literally, it means afterthought, changing one’s mind about someone or something. In ancient times, Metanoia was depicted as a shadowy goddess, cloaked and sorrowful, accompanying Kairos, the god of Opportunity, sowing regret and inspiring repentance for the “missed moment.” We can no longer afford to miss many more opportunities to change our destructive way of live and address the destruction of our planet. In the meantime, let us give generously to the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese and other community groups’ fire appeals and agitate for much needed change.