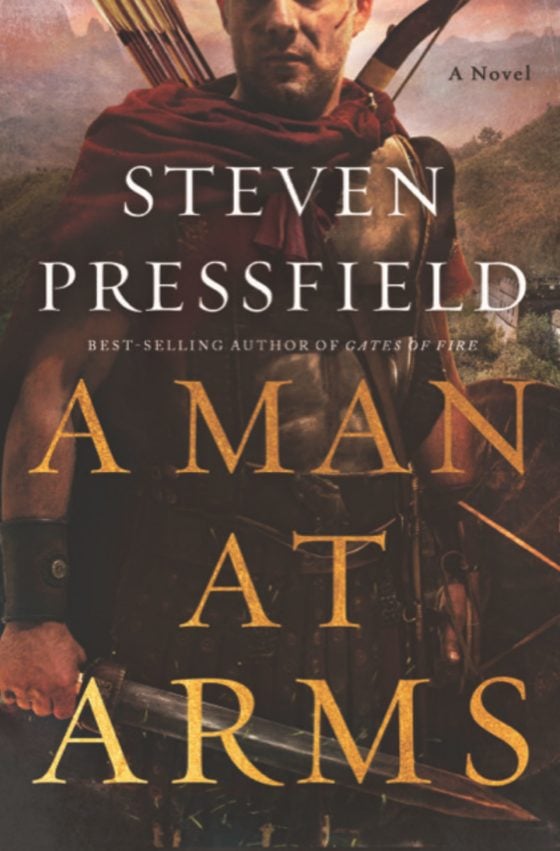

Steven Pressfield’s latest book A Man At Arms is set in Jerusalem and the Sinai desert around the first century CE when Judea was under Roman occupation. Telamon of Arcadia a former Roman commander, is charged with protecting an off-beat squad trying to deliver one of Paul’s (Saul) Letters to the Corinthians.

The legionary is guiding an impoverished mute girl, her barely alive father, a grungy zealot ‘witch’ with ambiguous aims, and an enthusiastic, albeit naïve, young man.

The lone wolf

Telamon of Arcadia is from a poor backwater in the Peloponnese and yet he emerges as a citizen of Pax Romana regardless of his lowly beginnings. He represents Rome, the first multiethnic citizens’ state and empire.

Mr Pressfield is cautious about notions of patriotism and idealism.

“Rome was the only game in town… if you were a poor boy from Spain or Germania, you enlist in the Roman Legions, or the Auxiliaries, because it’s a way out of grinding poverty… the army will take you on an adventure … give you something, a sense of belonging,” he said.

“I think of myself as a warrior… in the inner war of the heart”

Steven Pressfield

“We live in a consumer culture, the ancient world was never like that, the only way a poor kid from the Roman Empire could aspire to better themselves, was to enlist and go off and participate in campaigns… come back with loot and honour, a pension and farm granted by the state.”

Telamon is driven by a deeper personal code of conduct. Like an “old western gunfighter”, the lone wolf is forced back into action by honour and the desire to live on the edge.

“When the man at arms is asked which god he worships, he says Ares, the god of strife,” Mr Pressfield said.

Telamon protects the group through the desert while duplicitous Romans (chock-full of cruelty), mercenary Arab assassins and Jewish revolutionary guerrillas hunt them. If that’s not enough, they confront bees, fierce dust storms, spiny bushes, and sheer cliffs.

“A Man At Arms” is full of breathless action. It is like all Mr Pressfield’s books, well researched, and an authentic assessment of the ancient world. The powerful Roman Empire is showing cracks. Rebellion, urban terrorism, corresponding Roman subjugation in Judea and Palestine seem the norm. Fear has gripped the populace.

READ MORE: The Cave podcast: Ancient Thebans derided as yokels by the “snooty Athenians”

Warrior Ethos and the Ritual of Combat

The ‘warrior ethos’ is at the centre of much of Mr Pressfield’s work.

“I examine virtues that a solitary artist also needs to have,” he said, adding they are “like the virtues of a warrior – courage, patience, selflessness, and a love of other human beings, in a writer’s case, his characters”.

Warrior virtues are about “all the shit in life that we go through,” he adds.

“I think of myself as a warrior… in the war of the heart, I never planned to write historical novels, then I found myself writing Gates of Fire, then another book in the same vein and another… it’s a mystery that comes from the writer’s challenge… that inner war.”

Mr Pressfield has also written non-fiction books on art; “The War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles” and “The Warrior Ethos” among others.

“We operate on warrior principles, we might not be trying to kill others, but we are holding ourselves to a standard of ethics, a standard of honour, and a standard of aspiration for excellence in performance”.

He makes the natural link between warrior and athlete, “an athlete is a warrior.”

“An athlete doesn’t kill but is in the arena, and like an artist, they are always seeking to strive for excellence against all odds.”

“The Man At Arms” has detailed descriptions of weapons and Roman martial arts. The fight scenes are bone jarring. Military historian John Keegan suggested that close quarter combat was more just and far less destructive than the long-distance wars where one does not see the enemy.

READ MORE: Christos Tsiolkas talks about ‘Damascus’: The dawn of a new creed

New technologies, bows and arrows, lancets, catapults, bullets, missiles, and drones are impersonal, do little for the warrior ethos and more likely to cause civilian casualties.

“The ancient Greek concept of warfare was that if you were going to kill, you had to be so close to your enemy, so that they had a chance to kill you, anything less than that, even javelins, or archery – even though Apollo was the Archer God – was a lesser way of participating in the ritual of combat.”

When a drone is directed from vast distances, the concept of honour, as it was in ancient warfare is pretty much gone.

Beware self-sabotage

Mr Pressfield acknowledges that the warrior code can go awry if not constrained by ethics, duty, and honour. The warrior should emerge as a sage in old age.

In citizen armies the warrior should not obey immoral orders. The democratic soldier can take independent, moral, and heroic action, even against the orders of his/her superiors.

Mr Pressfield has no time for the ‘resistance’ or self-sabotage that infected the treacherous mobs that broke into Capitol Hill.

“Resistance,” he writes on his blog, “will kill you like cancer and make you commit acts that, seen in the light of reflection, you would be ashamed of and appalled by.

“Are you ‘special’? Are you ‘real’? Then everyone else is too. Those infected by this ‘resistance’ … “may come to believe that they can press their knee on George Floyd’s neck until he can no longer breathe.

“Because, on some deep level, they believe that they are “real” Americans, and that George Floyd is not.”

Steven Pressfield’s Telamon, in A Man At Arms, offers an antidote to faux masculinity. Telamon is the archetype of the warrior with a a code born of honour and love. For copies and more on A Man At Arms go to https://stevenpressfield.com