Owning a home (or two) has been seared into our immigrant psyche. Homeownership shielded our poor working-class immigrant parents from political and economic vagaries.

Unlike our Greek peers in Germany, home ownership meant we did not become permanent foreigners, or Ausländers.

Homeownership ensured cultural safety from bigotry and greater civic engagement. It also safeguarded the future of our second-generation immigrants born in Australia. It is less likely to do so for the third generation as the second-generation ages, had fewer children and will need their now high valued houses to buffer for their ageing, according to Kosmo Samaras strategist and demographer from RedBridge Group.

According to ABS Census, in 2021, “there were nearly 9.8 million households in Australia, 67 per cent were homeowners. In addition, lending commitments to owner-occupier first-home buyers increased from around 81,650 commitments in 2017 to 138,400 in May 2022.

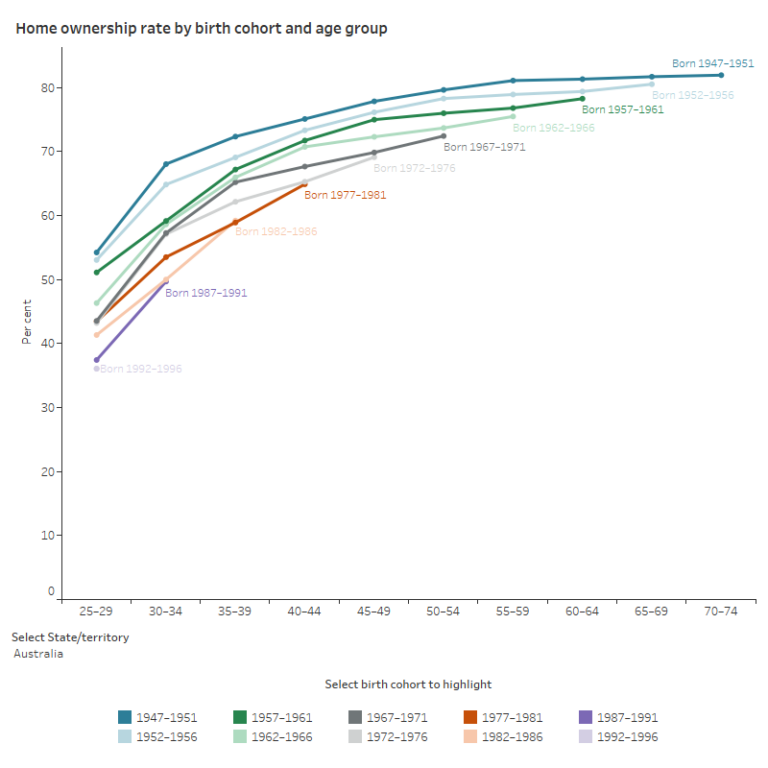

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AHIW) shows that successive generations of Australians tend to be less represented in home ownership. For example 73 per cent of those born between 1947 and 1951, Baby Boomers, owned their own home in the 1986 Census, while 67 per cent of those born between 1962 and 1966, Gen Jones, owned a home in the 1997 Census, and 53.5 per cent of those born between 1977 and 1981, Millennials, owned their own home at the 2011 Census.

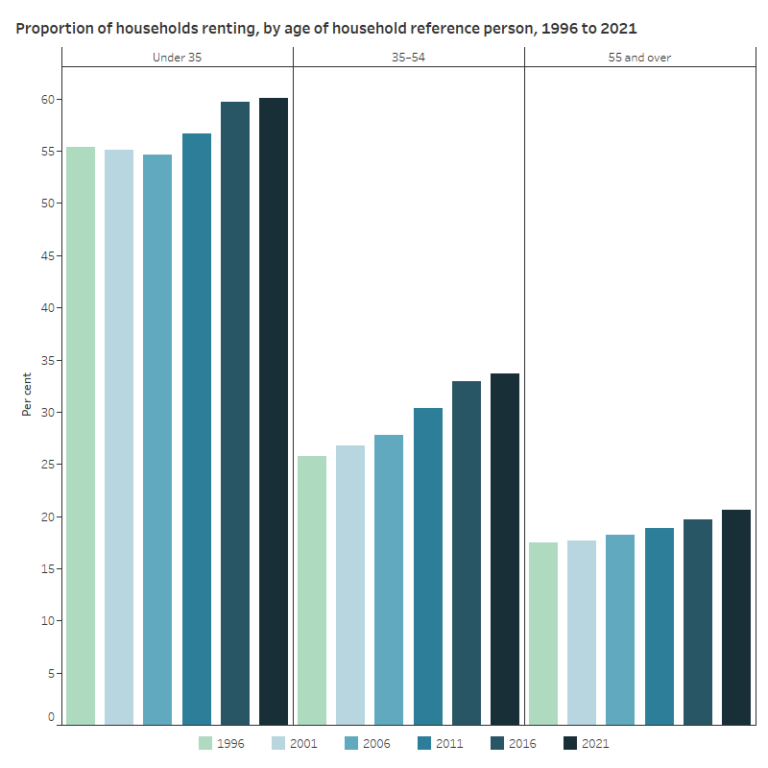

Renters have increased to around 30 per cent from 27 per cent over the last ten years, according to the ABS and mostly in the private market. And up to 35 per cent of a renter’s income now goes to rent.

There is consensus that we are facing housing and rental stress; however, the reasons are complex, as are the touted solutions.

Low supply of housing

A low supply of private, social, and affordable housing is a crucial factor all agree on. Australia is unique in that most of the housing is private, as is rental stock.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese recently agreed with states to limit yearly rental charge hikes. Labor’s initiative, the Housing Australia Future Fund, HAFF, earmarked $10 billion to stimulate additional housing construction.

However, the Greens and the Coalition in the Senate have become a stumbling block to Labor’s housing policy, with the prime minister threatening a double dissolution if the HAFF is not passed.

Max Chandler-Mather, the Greens housing spokesperson, wants “rental caps” along with increased housing supply and dismissed the prime minister’s double dissolution threat as an “empty threat.”

He told Neos Kosmos that the Greens “didn’t block” the policy. Instead, they “voted to defer consideration of the Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) to October 16,” aiming for negotiation time and awaiting a national inquiry’s findings on the rental crisis.

“62 per cent of renters, and over one-third of the country’s population, are facing financial stress,” with predicted faster rent increases, according to the Reserve Bank of Australia.

Chandler-Mather stressed the need for “rental caps.”

Chandler-Mather says that “we’ve witnessed some of the fastest rent increases in 35 years over the last two years,” with the “fastest quarterly increase since 1988. His assertion is based on quarterly data; many experts suggest it requires more context.

On an annualised basis, rents over the year to the end of June increased by 6.7 per cent, below the 8.4 per cent increase recorded over the year to December 2008 — almost 15 years ago. The spike in the cost of rentals that the Greens senator talks of was preceded by over a decade of negative growth in rents.

According to the Reserve Bank of Australia, most renters tend to be younger. Around half tend to be 25-44 years of age, and single older women are the ‘fastest rising group’ in public housing. According to Kosmo Samaras, new economic migrants living in the outer suburbs are also a significant cohort. Household composition changes have also impacted, according to AHIW, families with no or fewer children and more people living alone.”The demographics of renters are changing. The senator said that there’s “an increase in middle-aged and older renters”, and “regardless, we should not pass moral judgement on someone’s age.”

“We shouldn’t be saying that someone doesn’t matter because they are old,” Chandler-Mather said.

Discussions of migrant family composition, and the pooling of resources across generations, and kin, or the cultural weight of living at home as a young adult, until there was financial capacity to purchase a home, or unit, did not dissuade the senator from his position.

However, the AHIW still points to the most significant proportion of renters in 2021 as under 35 at 60.1 per cent and only 20.6 per cent were 55 + years old.

Samaras, told Neos Kosmos that according to the ABS, 37 per cent of all residents “who speak another language at home rent, 43 per cent have a mortgage, and 20 per cent own a home outright.”

He added, “28 per cent who only speak English at home rent, and 44 per cent have a mortgage while 28 per cent own a home outright.”

Those immigrants facing rental hardship tend to be “economic migrants” in the outer suburbs of the big cities, not new skilled arrivals.

Greens rental caps – ideological or essential?

Rental capping is a contentious issue, and most governments will not go down that path for fear of dampening investment in housing.

Mike Zorbas, Chief Executive of the Property Council of Australia, told Neos Kosmos that “rent capping is code for reducing housing supply and has long been discredited overseas.”

“As the Brookings Institute research finds, rent capping in the United States,… decreases affordability, fuels gentrification and creates negative externalities on the surrounding neighbourhood’.

Zorbas said that the “housing deficit was caused by 20 years of inaction at all levels of government.”

“The best solution to drive down the cost of at-market, social and affordable housing, whether to own or to rent, remains strong state housing targets, creating incentives for more supply and fixing broken state planning systems.”

He called on governments to unfreeze precinct plans and housing supply through the state planning authorities.

“We need to boost helpful asset classes like purpose-built student accommodation, retirement living communities and build-to-rent housing,” said Zorbas.

“The government has many workable policy options on the table that can create more supply and put downward pressure on owning and renting homes without adopting the Green’s cap and tax agenda that will hurt Victorians across every housing market,” Zorbas told Neos Kosmos.

Steve Maras, Managing Director, and CEO of the Maras Group in South Australia echoed that sentiment.

“Rent caps are a harsh measure for property investors and act as a disincentive to investment, and governments needs to stop taking the easy way out and constantly targeting private investors who too have financial commitments to honour.”

Dr Professor Ameeta Jain, the Senior Lecturer in the Department of Finance at Deakin University, reveals that over 80 per cent of property investors are small, with one investment house and one they live in. Of the “2.5 million Australians” with investment properties, “1.5 million” own one property and residence. Only around 150,000 or so own six or more properties.

She points to the low return on investment and maintenance cost; the landlords, she writes, “invest substantial sums of money in construction and maintenance to meet the legislative standards for rental properties.”

The overwhelming number of “investors and landlords” are general managers, teachers, nurses, accountants, childcare workers, mechanics, truck drivers, and police officers. The return after maintenance is only “3 to 7 per cent.”

Dr Jain also believes that rent caps will disadvantage “battling families” in the rental market as landlords will prefer professionals. Chandler-Mather refuted this and said that rent caps would “slow skyrocketing house prices and benefit middle-income families concerned about their children’s homeownership prospects.”

He rejected the argument that the overwhelming number of investors earn less than $100,000. Whilst Dr Jain says that small investors earn around $8,200 per year, Chandler-Mather pointed to “negative gearing” and its “impact, allowing tax write-offs on investment losses.”

Dr Jain points to evidence in Britain where rent caps forced houses to fall into disrepair. Also landlords withdrew their property from the rental market and put it up for sale. Something that the Green senator welcomes.

“Isn’t it a good thing that a rental property goes for sale, that means that someone who is renting can now buy,” he said.

Regarding migrants’ desire and need to buy an additional property to buffer economic hardship, Chandler-Mather said, “Renters cannot write off the rent increase on tax.”

“Why does the rental caps debate focus on property investors and landlords?

“If all this Greek migration were today [sic], they would not be able to do the same thing they did when they arrived,” said Chandler-Mather.

Political analyst George Magalogenis wrote that Australia is experiencing the most significant wave of skilled, middle-class migration since the mid-19th century – from ‘India, China, South Africa, and the Philippines to work as doctors and nurses, human resources and marketing professionals, business managers, IT specialists, and engineers.”

Post-war immigrants started on the “lower rungs of the income ladder, and we measured their integration through their uptake of small business and home ownership and the success of their Australian-born children through education.” said Megalogenis in The Sydney Morning Herald.

“I do not want to debate, but I am happy to provide lines,” Chandler-Mather said.

When Neos Kosmos presented the senator with the view, based on research, that since the post-war period, including the last ABS Census, migrants view housing as an essential aspect of development and futureproofing, the senator chided back, “You know who else wants a house? Renters.”

When asked if immigrants would be looking to housing as an investment for themselves and their children, Chandler-Mather responded: “They can invest in shares if they want.”