‘Damascus’ is Christos Tsiolkas’ most demanding book. Based on Paul’s transformation from Saul and his travels, the novel seeps into one’s skin. It draws out dreams and creates sleepless nights.

Written from various perspectives of the key actors, ‘Damascus’ begins with Lydia, an old Greek woman who was once young and middle class. She now lives in a cave and many see her as a witch. Lydia prays to Jesus over babies abandoned on the mountain by their Greek and Roman parents to die from exposure, or to be eaten by beasts.

“Man it takes balls to write like a woman now,” I say and we both fall apart in laughter at the madness.

“I did not think about that as an issue regardless of ‘woke’ puritans, I do not give a fuck,” Tsiolkas says.

“Initially Lydia was written as her slave Goodness, but she would not have entry into the world of the Greeks and Romans.

“And once I decided to do so, the chapters came out as a rush, I wanted to say it from the perspective of a woman because the early Christian fellowship had erased women yet they played a pivotal role.

“She’s a Greek and open to learning, Lydia goes to hear the ‘word’ at the meetinghouse,” says Tsiolkas.

In ancient Judea Greeks attended the Synagogues regardless of not being Jewish.

“The Greeks were called ‘god fearers’ by the Jews, regardless of not being Jewish.”

Greeks had an Unknown God, the Agnostos Theos. It was this god that Apostle Paul talks about to the Athenians in Areopagos sermon.

It was in a new religion Christianity that women, children, slaves became ‘brothers and sisters’. It was a radical religion that saw them as equals. Paul and the apostles seeded the collapse of the Greco-Roman world, with a new Judaic-Hellenistic philosophy, Christianity.

Paul needed the Greeks for the Roman world collapse. The Zealots could not do it alone. The final war against the Romans by the Zealots brings is the end of Jerusalem as the Romans turn the city to ash.

“You cannot read Paul’s sermons and letters and not see Plato in them,” Tsiolkas adds.

Greeks reconcile the pagan and the Christian, the feminine and the masculine.

“Nikos Kazantzakis talks about that the division of the feminine and the masculine, Nietzsche sees Christianity as feminine, a slave religion,” he says.

When we enter the world through Saul’s eyes – before he became Paul – as a radical Jew hunting down Jews that forsook the law of god, we feel Saul’s indignity and final rapture – that white light that burned into him on the way to Damascus.

Saul he is anguished by his own sexuality, his eroticism.

“That was my way into him, finding out about him as a character, I was not interested in the saint, I was interested in the man.

“That is why my first couple of attempts were failures because I thought of him as a saint, but no, he is a man.”

READ MORE: Christos Tsiolkas: ‘If you can’t see the humanity in the other person then I’m scared of you’

About shame

Tsiolkas, like all Greeks and Jews, like all easterners, knows shame.

“I understand shame culture which is very different to the guilt culture of the Protestants and some of the Catholics,” he says.

“As Greeks, and Orthodox, we are from the east, we know the deeper connection to a pre-Christian world, we have no guilt, but we know shame.”

You feel shame when an act is exposed to your family, clan and village. Yet we feel no guilt, we have no guilt.

“You can be in Amman in Jordan and the eroticism is palpable compared to the west, even among men.”

On one chapter, Vrasas the Roman who cares for the imprisoned Paul, even calls him ‘uncle’, does not understand his weakness. His Rome will not succumb to Christianity, a religion he views as weakness.

Rome was a democratising empire. Anyone could be Roman regardless of colour and faith as long as you hail the ‘first among equals’ and believed in Rome.

“As Greeks, and Orthodox, we are from the east, we know the deeper connection to a pre-Christian world, we have no guilt, but we know shame.”

Vrasas drags Paul to witness the Roman apex of cruelty, the games, cannot understand anyone that could forsake Pax Romana for the ‘corpse god’.

Tsiolkas pulls out a gold cross hanging from his neck “my Aunty Yianoula gave me this when I was 21yrs old.”

“Now I think that this man, a representative of god, is humiliated, tortured, flayed, and killed in public and then over him a new system and thought develops… it is extraordinary.”

“You remind me of Vrasas,” he laughs. I am flattered. I am a Roman.

‘Damascus’ is visceral it can be smelt and felt.

“I travelled to Jerusalem, to Antioch, I wanted to walk those places, to smell, to draw on them as a writer,” he says.

“The hardest thing is to write about a man of 2000 years ago they weren’t us, but also like us.

“Our over-dependence on postmodernism damaged our view of the past.”

Tsiolkas points to John Boswell’s work on sexuality in the early church, a gay man who died of AIDS.

Postmodernism is a dangerous problem as it gnaws away on history.

“Boswell was a great scholar and deeply thoughtful theologian, yet I remember peers at uni telling me ‘don’t read that Foucault hated it’ why? Because he talks about love.”

Tsiolkas has no fear talking about the public intellectual Jordan Petersen who has caused so much controversy by not bending to authority; “The number of arguments I have had with people about that man” he sighs.

“I love listening to his analysis of bible stories, he is a classical Jungian and his analysis of Cain and Abel is fantastic”

“People say ‘how can you listen to him he’s blah, blah…’ and I say ‘I may not agree with him on everything, but I am interested in what he has to say.’

“When we were at uni he would have been a smart conservative Jungian thinker, why such vitriol towards him?

“He has become a hero only because we have allowed that to happen, because we are so scared to talk about anything and we know less and less about history.”

Tsiolkas likens Peterson to Joseph Campbell, the American Professor of Literature known for his groundbreaking work in comparative mythology and religions, who developed the notion of the archetypal hero.

“I guess not many read Campbell now, or they would denounce him as well,” he laments.

Denouncing, cancelling, attacking in public, is what they did to Paul, Jesus and others 2000 years ago; we are not so different after all.

Tsiolkas tries to make sense of a “human Paul and a human Jesus” in Damascus.

He does not believe in Jesus the god, or the resurrection, but he recognises the immense moral and ethical impact of Judaism and Christianity.

“I love much in Christian ethics but I do not love the division between the flesh and the soul.”

Tsiolkas associates with Timothy. “He has a Jewish mother and the Greek pagan father I attempted to reconcile the two sides, Judaism and Hellenism,” he says.

READ MORE: The controversial ‘gods’ of Tsiolkas

Transcending time

‘Damascus’ is about now as much as it was about 2000 years ago. We see in it masses of refugees leaving a blood-soaked burning Jerusalem, after the Romans level it, speaking in Syrian, protected by early Christians.

“Young woke and old woke people have a limited knowledge of history… like what do you mean when you say ‘white’? What is a Georgian? What colour is a Lebanese person? Why is a Greek white, and a Turk not?” he asks.

Tsiolkas has shaken off his Marxism, “I am no longer a Marxist you cannot look at the 20th Century and still be a Marxist.”

“One thing that I have set for myself in 2020 is to read Adam Smith.

“I did not reason Adam Smith in my uni years, not because Marx did not like him, Marx refers to him in his works, I never read Smith at uni was because of some fucking lecturer said that it would corrupt me – its so bloody religious.”

Tsiolkas likens Marx to Judaism and Christianity; “How can you understand ethics without Judaism and Christianity and how can you understand capitalism without Marx?” he asks.

“We are in a dangerous period where people no longer know history.”

READ MORE: Tsiolkas up for top literature prize

Tsiolkas points to Greta Thunberg “she is Martin Luther’s interpretation, through Paul, of morality and I ask how do we not know this right now?”

“Have we forgot the real danger of the Puritans who burned churches and smashed icons? Have we forgotten the Incorruptible Robespierre who filled the streets of France with blood?”

“Have the new intellectuals not read about the Committee of Public Safety? Clearly not given the mob amassing on social media and the cancel culture of now.

For Tsiolkas Paul is “most important for the Protestants, the Puritans, he’s not for the Catholics Peter is for the Catholics.”

“Puritans hah… I detested them in the left, and anywhere they enter–over-righteous, fanatical, and ready with violence look at Robespierre, Pol Pot and others.

“It is easy to call them monsters, but Pol Pot was educated in France, he was aware, and their mission and righteousness make them do horrific things.”

‘Damascus’ forced me to buy the Bible. I want to read a foundational text again. So when I entered Readings in Carlton and asked a man working there if Paul’s letters to the Corinthians was in the Bible, or if I had to buy the New Testament, he laughed, “Ha…I wouldn’t know, I’m the last person to ask”

“Strange,” I thought, given Readings’ shop window was dressed with Tsiolkas’ Damascus – a novel on the life of Paul.

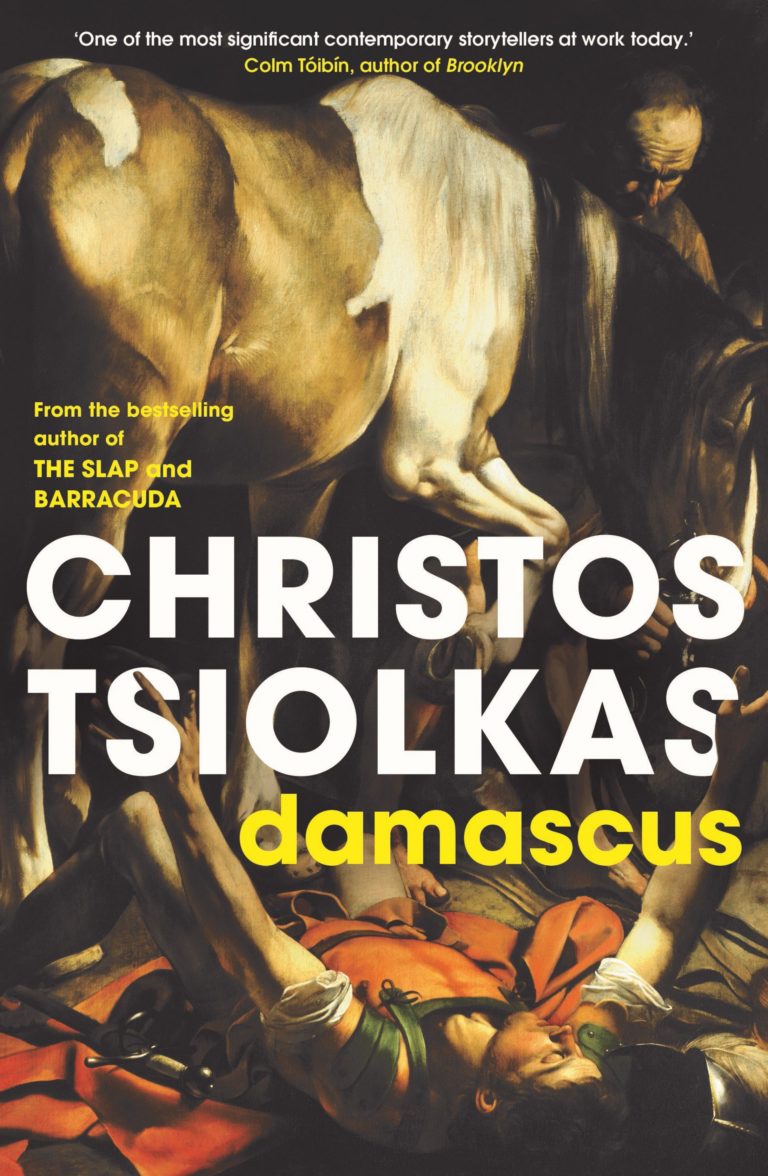

‘Damascus’ by Christos Tsiolkas is published by Allen & Unwin, $32.99